Bessie Smith

PerformerBessie Smith was one of the most important blues artists of the 1920s. Having grown up in poverty, Smith performed as a young girl on the streets of Chattanooga, Tennessee. She was singing, dancing and telling jokes on vaudeville stages by the time she was a teenager, debuting in Atlanta’s “81” theater in 1909. Smith gained a loyal following throughout the South, but by 1922 she had moved north to Philadelphia and turned her attention to the recording boom of the “blues.” She was initially rejected by OKeh Records and Black Swan Records, a Black-owned record company, for being “too rough” – essentially for being too Black, too unrespectable. However, white talent scout Frank Walker at Columbia Records was impressed with Smith’s vocals, particularly by the “torture and torment she put into the music of her people.” Columbia signed Smith in 1923, and following her first recording, “Down Hearted Blues,” she quickly became one of the most prominent artists in the company’s new “race” category. Smith went on to record hundreds of songs, including hits like “Back-Water Blues,” “Need a Little Sugar in My Bowl,” and “Nobody Knows You When You’re Down and Out.” Dubbed the “Empress of the Blues,” she helped inject the new genre with a “down-home,” southern style.

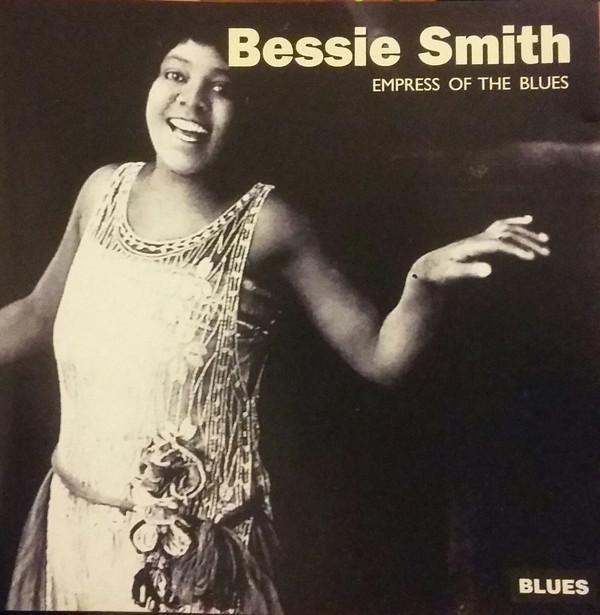

Smith’s star power was built on an unlikely combination: a powerful vocal style, gritty lyrics, and dressy glamour. She belted out relatable, often salacious songs while dressed in extravagant gowns, furs, and headdresses. Although white southerners typically preferred black performers who conformed to Mammy and Uncle Tom stereotypes, many seemed to enjoy Smith’s flashy costumes and suggestive movements as well as her use of slapstick humor derived from vaudeville. Nevertheless, working-class African Americans in the North and South constituted her primary audience. Smith’s songs spoke directly to the everyday struggles and concerns of these listeners, addressing homelessness, poverty and domestic abuse and, often, directly expressing and celebrating female sexual desire.

Smith used her public performances, private life, and song lyrics to challenge racism in the U.S. and sexism within the African American community. She carried on bisexual affairs in public view, had a larger body type than most female performers, and was considered both musically and socially defiant. Her songs “I’m Wild About That Thing,” “You’ve Got to Give Me Some,” and “Kitchen Man” constructed her as an unabashedly confident and sexually aggressive woman. In all of these ways, Smith provided an alternative model of how Black women in the U.S. could look and act.

Bessie Smith created a musical and performative space where sexual, racial, and gendered realities were not regulated by the state or shamed by black religious and bourgeois communities. After her death resulting from a car accident in 1937, she continued to be an icon for black women and gay and lesbian communities in the U.S.

Smith’s star power was built on an unlikely combination: a powerful vocal style, gritty lyrics, and dressy glamour. She belted out relatable, often salacious songs while dressed in extravagant gowns, furs, and headdresses. Although white southerners typically preferred black performers who conformed to Mammy and Uncle Tom stereotypes, many seemed to enjoy Smith’s flashy costumes and suggestive movements as well as her use of slapstick humor derived from vaudeville. Nevertheless, working-class African Americans in the North and South constituted her primary audience. Smith’s songs spoke directly to the everyday struggles and concerns of these listeners, addressing homelessness, poverty and domestic abuse and, often, directly expressing and celebrating female sexual desire.

Smith used her public performances, private life, and song lyrics to challenge racism in the U.S. and sexism within the African American community. She carried on bisexual affairs in public view, had a larger body type than most female performers, and was considered both musically and socially defiant. Her songs “I’m Wild About That Thing,” “You’ve Got to Give Me Some,” and “Kitchen Man” constructed her as an unabashedly confident and sexually aggressive woman. In all of these ways, Smith provided an alternative model of how Black women in the U.S. could look and act.

Bessie Smith created a musical and performative space where sexual, racial, and gendered realities were not regulated by the state or shamed by black religious and bourgeois communities. After her death resulting from a car accident in 1937, she continued to be an icon for black women and gay and lesbian communities in the U.S.