Mamie Smith

PerformerPioneering performer and singer Mamie Robinson Smith was the first black singer to record the blues. Born in Cincinnati, Ohio, Smith began her career on stage at the age of ten, performing in segregated vaudeville and minstrel shows.

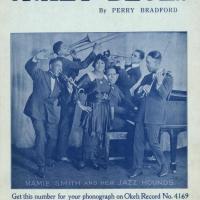

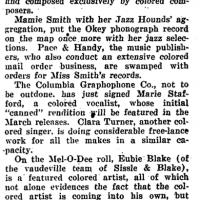

Smith was a mainstay of the New York stage. In 1918, she was cast in songwriter Perry Bradford’s musical revue “The Maid of Harlem.” The collaboration between Bradford and Smith had lasting effects; in looking for a new recording artist, Bradford felt Smith’s talents would be successful in the record market. Thus, in February of 1920, Smith recorded the songs “That Thing Called Love” and “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,” after Bradford convinced Okeh records to produce them. Six months later, Smith’s hit “Crazy Blues” became a crazy success, selling over one million records in a year’s time, many bought by black Americans. Daphne Duval Harrison, author of Black Pearls writes that the record “set off a recording boom that was previously unheard of,” and that her success finally convinced the record companies that there was a viable “market in the black community.”

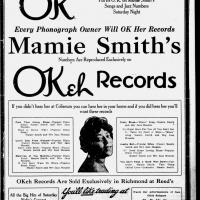

Harrison writes that Okeh’s successor, the General Phonograph Corporation, began promoting Smith’s recordings by linking them to her stage appearances, which ended up being a successful strategy that boosted both her stage and recording careers. According to Harrison, Smith “set a standard for the blues queens who followed her with her lavish costumes and scenery.”

Mamie Smith’s impact on American music cannot be overstated. In addition to being the first recorded black blues singer, the success of her early records in black communities opened the floodgates to so-called “race records,” which convinced other record labels to record black artists. Furthermore, Harrison argues that “Smith’s artistic versatility led her to becoming what we might think of as a curatorial bridge figure of sorts whose “Crazy Blues” connected Black musical theater to evolving blues culture, Northern theater aesthetics to the faint yet felt traces of Southern jook sound, and the aesthetics of the “coon shouter”—that repugnant label for late nineteenth and early twentieth-century white minstrel popsters—folding it all into Black women’s popular music vocalities.” Daphne Brooks writes that "Mamie’s smash calls out to us to rethink our standard narratives of the blues as well as the gutsy complexity of Black women’s musicianship more broadly."

Smith was a mainstay of the New York stage. In 1918, she was cast in songwriter Perry Bradford’s musical revue “The Maid of Harlem.” The collaboration between Bradford and Smith had lasting effects; in looking for a new recording artist, Bradford felt Smith’s talents would be successful in the record market. Thus, in February of 1920, Smith recorded the songs “That Thing Called Love” and “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,” after Bradford convinced Okeh records to produce them. Six months later, Smith’s hit “Crazy Blues” became a crazy success, selling over one million records in a year’s time, many bought by black Americans. Daphne Duval Harrison, author of Black Pearls writes that the record “set off a recording boom that was previously unheard of,” and that her success finally convinced the record companies that there was a viable “market in the black community.”

Harrison writes that Okeh’s successor, the General Phonograph Corporation, began promoting Smith’s recordings by linking them to her stage appearances, which ended up being a successful strategy that boosted both her stage and recording careers. According to Harrison, Smith “set a standard for the blues queens who followed her with her lavish costumes and scenery.”

Mamie Smith’s impact on American music cannot be overstated. In addition to being the first recorded black blues singer, the success of her early records in black communities opened the floodgates to so-called “race records,” which convinced other record labels to record black artists. Furthermore, Harrison argues that “Smith’s artistic versatility led her to becoming what we might think of as a curatorial bridge figure of sorts whose “Crazy Blues” connected Black musical theater to evolving blues culture, Northern theater aesthetics to the faint yet felt traces of Southern jook sound, and the aesthetics of the “coon shouter”—that repugnant label for late nineteenth and early twentieth-century white minstrel popsters—folding it all into Black women’s popular music vocalities.” Daphne Brooks writes that "Mamie’s smash calls out to us to rethink our standard narratives of the blues as well as the gutsy complexity of Black women’s musicianship more broadly."