I Ain't Got Nobody Much

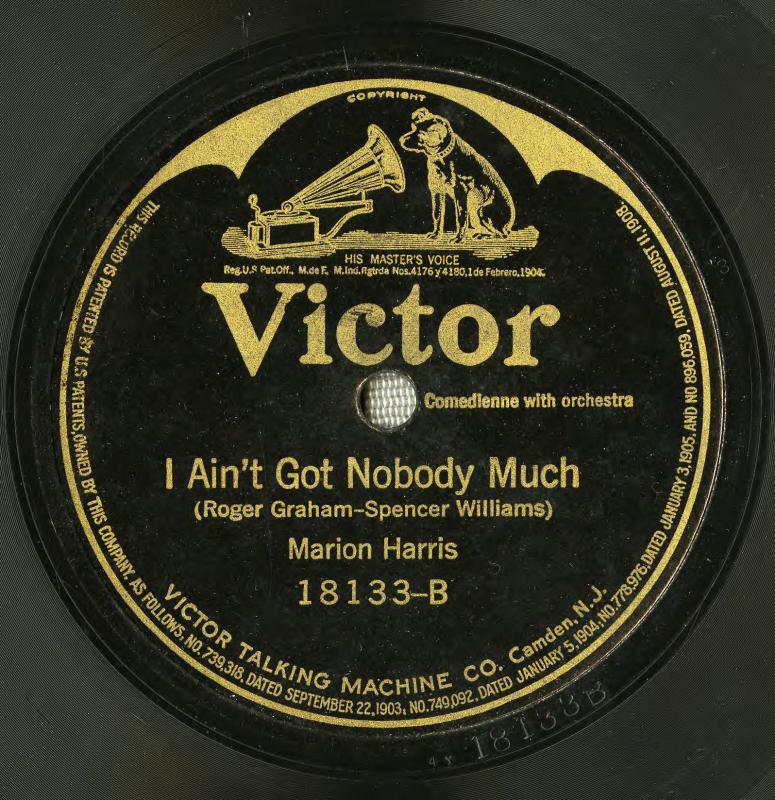

jazz, bluesThe different versions of the song “I Ain’t Got Nobody” reflect the evolution of blues music in the early twentieth century. With music and lyrics by Spencer Williams and Roger Graham, “I Ain’t Got Nobody Much,” as it was originally called, was first recorded by Marion Harris for Victor in 1916. Harris, who was white, began her career singing in vaudeville shows in Chicago. She became known as a specialist in blues in the mid-1910s thanks to her ability to imitate African American dialect and speech patterns. One of Harris’s most popular songs, “I Ain’t Got Nobody Much” reveals the way the blues genre emerged from within vaudeville.

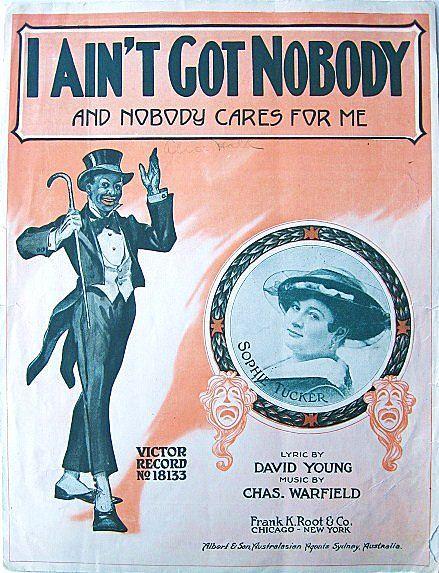

“I Ain’t Got Nobody Much” may also reflect the influence of Bert Williams’ minstrel number, “Nobody.” Recorded in 1906 and popularly performed by the Afro-Bahamian Williams in blackface, “Nobody” parodied the “sad negro” genre, in which white performers in blackface sang about their troubles and woes. In “Nobody,” Williams bends pitches and notes, slurs to imitate a trombone, and sings comically about going home and finding “nobody.” White and black audiences loved his comedic performance, laughing hysterically at Williams’ exaggerated pain. But Harris’s interpretation ten years later suggests that white people also perceived black parodies of minstrelsy to be authentic black music. In “I Ain’t Got Nobody Much,” Harris mimics the authentic blackness in performances like Williams’ by repeating the word “ain’t,” accentuating the melisma in “nobody” and “lonely,” and evoking the themes of loneliness and weariness. White misreading and re-appropriation of black parody extended the legacy of minstrelsy; for example, the minstrel imagery used on the sheet music cover for Sophie Tucker’s 1927 version depicts a man in blackface and a tuxedo with a comedic flair, directly invoking the minstrel show.

“I Ain’t Got Nobody” continued to evolve through multiple reappropriations. By the mid-1920s, a number of black artists had covered the song, popularizing it even more than its original recording. Famous blues queens, such as Bessie Smith and Ida Cox, recorded covers, keeping the same lyrics but adding components such as a bigger, belting vocal style and an emphasis on trumpet, clarinet, and banjo. Smith’s 1925 recording featured a piano blues shuffle rhythm, extensive improvisation and a stop-time, syncopated accompaniment behind the first line of the chorus. As such, it would have sounded like “jazz” to listeners of the time. Interestingly, this version also included a banjo, which was still associated with blackness and the minstrel show but would soon become a symbol of white hillbilly music. The differences between Smith’s and Harris’s versions, and the popularity of Smith’s version, illustrates the rise of “race records,” which pushed white vaudeville blues performers like Marion Harris out of the commercial music market by the mid-1920s. What began on the minstrel stage as a white parody of black music had been transformed by artists like Bessie Smith into a vibrant musical tradition that African Americans could enjoy on their own terms.

“I Ain’t Got Nobody Much” may also reflect the influence of Bert Williams’ minstrel number, “Nobody.” Recorded in 1906 and popularly performed by the Afro-Bahamian Williams in blackface, “Nobody” parodied the “sad negro” genre, in which white performers in blackface sang about their troubles and woes. In “Nobody,” Williams bends pitches and notes, slurs to imitate a trombone, and sings comically about going home and finding “nobody.” White and black audiences loved his comedic performance, laughing hysterically at Williams’ exaggerated pain. But Harris’s interpretation ten years later suggests that white people also perceived black parodies of minstrelsy to be authentic black music. In “I Ain’t Got Nobody Much,” Harris mimics the authentic blackness in performances like Williams’ by repeating the word “ain’t,” accentuating the melisma in “nobody” and “lonely,” and evoking the themes of loneliness and weariness. White misreading and re-appropriation of black parody extended the legacy of minstrelsy; for example, the minstrel imagery used on the sheet music cover for Sophie Tucker’s 1927 version depicts a man in blackface and a tuxedo with a comedic flair, directly invoking the minstrel show.

“I Ain’t Got Nobody” continued to evolve through multiple reappropriations. By the mid-1920s, a number of black artists had covered the song, popularizing it even more than its original recording. Famous blues queens, such as Bessie Smith and Ida Cox, recorded covers, keeping the same lyrics but adding components such as a bigger, belting vocal style and an emphasis on trumpet, clarinet, and banjo. Smith’s 1925 recording featured a piano blues shuffle rhythm, extensive improvisation and a stop-time, syncopated accompaniment behind the first line of the chorus. As such, it would have sounded like “jazz” to listeners of the time. Interestingly, this version also included a banjo, which was still associated with blackness and the minstrel show but would soon become a symbol of white hillbilly music. The differences between Smith’s and Harris’s versions, and the popularity of Smith’s version, illustrates the rise of “race records,” which pushed white vaudeville blues performers like Marion Harris out of the commercial music market by the mid-1920s. What began on the minstrel stage as a white parody of black music had been transformed by artists like Bessie Smith into a vibrant musical tradition that African Americans could enjoy on their own terms.