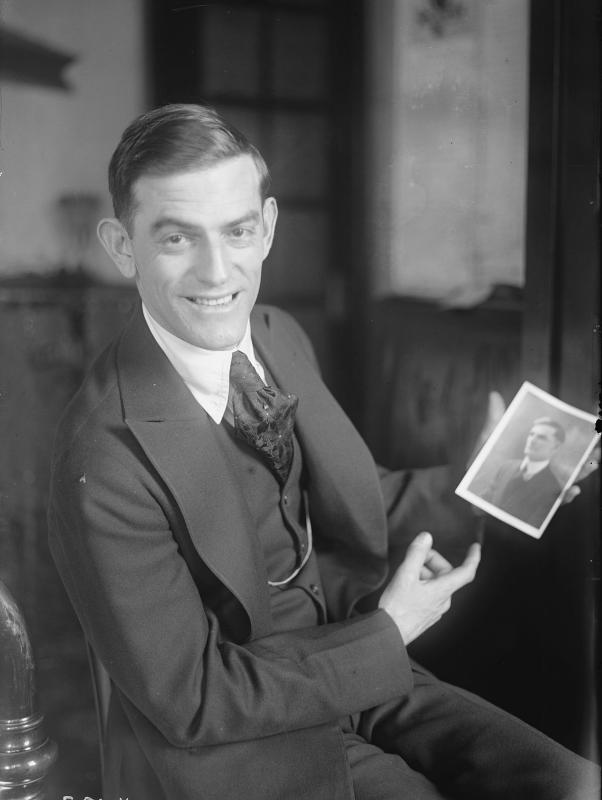

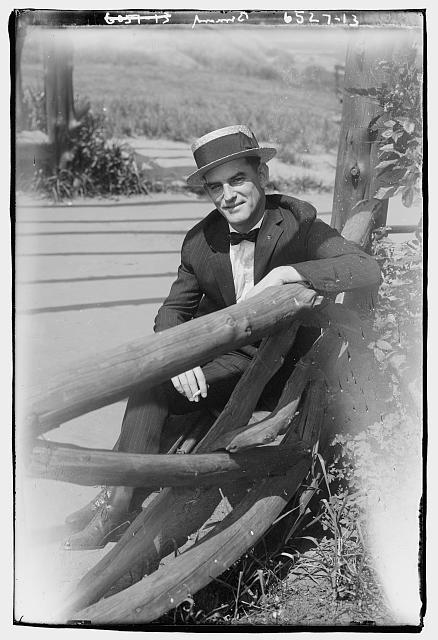

Al Bernard

PerformerAl Bernard played a key role in the development of genre recording and “the blues,” and his career shows how minstrelsy influenced nearly all popular music in the early twentieth century.

Bernard, born in Louisiana, began his career in minstrel shows, performing in blackface makeup. His stage act blended singing with comic skits and routines, and when he made the transition to recording he carried over both the imitation black dialect and the comedy. But his accent or style of singing won’t sound “black” to modern audiences--the sense of how black people are supposed to sing and talk has changed dramatically since the early twentieth century.

Bernard’s recordings, made mostly after WWI, focused on themes drawn from the minstrel show, which had featured both comic black characters and “sad negro” songs. Songs like “Strut Miss Lizzie” (https://hearingtheamericas.org/admin/item/937) might have come right off the minstrel stage, but he also recorded W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues” and "St. Louis Blues.”(https://hearingtheamericas.org/admin/media/942)

Bernard’s 1919 version of “Hesitation Blues” (https://hearingtheamericas.org/admin/item/939) offers an early example of a song that would become a standard in the repertoire of both black and white blues musicians. The backing band adds elaborate comic trombone slurs while Bernard affects his version of a black dialect. The song’s origins are obscure: Bernard’s was probably the first commercial recording

His career demonstrates how much of “blues” as a commercial genre began not in field hollers and rural culture, but in stage parodies and comedy. By the early twenties African American women like Bessie Smith came to dominate the field of the blues: Smith also came to blues via vaudeville but she sang in a very different style than Bernard, with fewer of the minstrel trappings.

Bernard, born in Louisiana, began his career in minstrel shows, performing in blackface makeup. His stage act blended singing with comic skits and routines, and when he made the transition to recording he carried over both the imitation black dialect and the comedy. But his accent or style of singing won’t sound “black” to modern audiences--the sense of how black people are supposed to sing and talk has changed dramatically since the early twentieth century.

Bernard’s recordings, made mostly after WWI, focused on themes drawn from the minstrel show, which had featured both comic black characters and “sad negro” songs. Songs like “Strut Miss Lizzie” (https://hearingtheamericas.org/admin/item/937) might have come right off the minstrel stage, but he also recorded W.C. Handy’s “Memphis Blues” and "St. Louis Blues.”(https://hearingtheamericas.org/admin/media/942)

Bernard’s 1919 version of “Hesitation Blues” (https://hearingtheamericas.org/admin/item/939) offers an early example of a song that would become a standard in the repertoire of both black and white blues musicians. The backing band adds elaborate comic trombone slurs while Bernard affects his version of a black dialect. The song’s origins are obscure: Bernard’s was probably the first commercial recording

His career demonstrates how much of “blues” as a commercial genre began not in field hollers and rural culture, but in stage parodies and comedy. By the early twenties African American women like Bessie Smith came to dominate the field of the blues: Smith also came to blues via vaudeville but she sang in a very different style than Bernard, with fewer of the minstrel trappings.