W.C. Handy

William Christopher Handy, known professionally as “W. C. Handy,” was one of the most important figures in early-twentieth-century music, but also one of the most difficult to characterize. His songs, especially “St. Louis Blues,” are among the most enduring legacies of the period, and his early compositions helped define “blues” as a genre. He combined dignified professionalism with minstrel trickery, and he had a keen understanding of his own place in history. He self-consciously worked to establish himself as “the father of the blues.”

Handy was born in 1873 In Florence, Alabama. His respectable, working-class family recognized his musical ability early, he recalled, but tried to steer him towards religious music, paying for lessons on the organ. Handy however joined a local brass band and concentrated on the cornet and trumpet. He worked semi-professionally as a musician until in the mid 1890s, when he joined “Mahara’s Colored Minstrels,” a touring minstrel show owned and operated by Irish immigrant brothers.

In his autobiography, "Father of the Blues," Handy recalled his pride at being the concertmaster of the band at age 23, able to quickly produce complicated arrangements of any new tune for as many as 42 band members. The successful troupe traveled in style but still had to protect itself against the ever-present dangers of racism. Their rail cars, Handy wrote, had a secret compartment under the floorboard with a stash of weapons, food and clothes in case of emergency. Handy briefly left the Maharas to teach music, then went back to touring with them for a short time in 1903.

Handy’s account of his time with the Maharas is revealing. He described how, when they first arrived in a town, they would parade down main street from the rail station:

In all probability, we would pull the “Musicians’ Strike” out of our bag of tricks. During this well-rehearsed feature each musician would, when his turn came, pretend to quarrel with someone else and quit the band in a huff. When, to the dismay of the innocent yokels, the band had dwindled to almost nothing, a policeman who had been “fixed” and planted at a convenient spot would come up and ask questions. This would lead to a fight between some of the remaining musicians, and the officer would promptly arrest them.

The crowd could be depended on to express its disappointment in strong language. “Just like n——-s,” they’d groan. “They break up everything with a fight. Damn it all, they’d break up Heaven.” During these recriminations we would spring the old hokum. The band, having reassembled around the comer, would cut loose with one of the most sizzling tunes of the day, perhaps Creole Belles, Georgia Camp Meeting, or A Hot Time In the Old Town Tonight, and presently the ticket seller would go to work. Our hokum hooked them.

Handy’s recollection shows the band playing to, and then cleverly subverting, racial stereotypes. in a manner similar to Bert Williams a few years later. The story also suggests his fondness for “hokum” and that we should not take his stories at face value. For example, his famous account of how he first heard the blues at a rural rail station in Tutwiler, Mississippi:

Then one night at Tutwiler, as I nodded in the railroad station while waiting for a train that had been delayed nine hours, life suddenly took me by the shoulder and wakened me with a start. A lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly.

Handy’s “lean, loose jointed negro” with his ragged clothes and toes sticking out of his shoes sounds exactly like the stock “Jim Crow” character from minstrel shows, and his reference to playing the guitar “in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists” points out this was not a folk musician Handy heard, but rather a musician familiar with the popular fad for commercial Hawaiian music.

He gave an equally slippery account of his first hit with “blues” in the title, the Memphis Blues.

It was perfectly natural that Pee Wee’s should become the headquarters for our band for a time at least, and in the fall of 1909 I often used to use his cigar stand to write out copies of the following lyric for visiting bands:

Mr. Crump won’t ’low no easy riders here

Mr. Crump won’t ’low no easy riders here

We don’t care what Mr. Crump don’t ’low

We gon’ to bar’1-house anyhow—

Mr. Crump can go and catch hisself some air!

The city was in the midst of a three-cornered campaign to elect a mayor, and our band was beating the drum for Mr. E. H. Crump, who was running on a strict reform platform. I had composed a special campaign tune for this purpose, but without words. We had played it, with success. Meanwhile I had heard various comments from the crowds around us, and even from my own men, which seemed to express their own feelings about reform. Most of these comments had been sung, impromptu, to my music. My lyric was based upon some of these spontaneous comments, with my own development and additions. Luckily for us, Mr. Crump himself didn’t hear us singing these words… Its musical setting, which I afterwards published under the new title “Memphis Blues,” was the first of all the many published “blues,” and it set a new fashion in American popular music and contributed to the rise of jazz, or, if you prefer, swing, and even boogie-woogie.

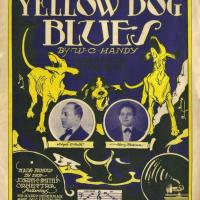

This story makes no sense at all: the lyrics he describes don’t fit the form of “Memphis Blues” in any way, but do fit the form of a traditional song known as “Mama Don’t Allow.” It positions Handy as a trickster: hired to support Crump’s campaign, he undermines it instead. But he also plays a trick on readers by claiming a relationship between two entirely different tunes. Handy here demonstrates the extremely mixed origins of one of the first blues songs ever recorded. Later, recognizing blues had become a fad, Handy would retitle his song “Yellow Dog Rag” as “Yellow Dog Blues” and watch as sales miraculously increased.

Father of the Blues was written in 1941, late in Handy’s life, when “blues” was well established as genre and when Handy knew that it was popularly understood as an expression of vernacular folk culture, not minstrel shows and political campaign songs. He wrote the autobiography in dialogue with Abbe Niles, a wealthy Wall Street lawyer and jazz enthusiast. Niles wrote music criticism and promoted the value of African American folk music: he pushed Handy to emphasize the folk origins of the blues. Niles wrote the introduction to Father of the Blues, a nickname Handy was happy to accept. At the same time Handy resisted Nile’s efforts to cast him as some sort of musical natural, born with blues in his soul because of his race. He wanted to make it clear he was a professional, capable of composing and scoring complex arrangements for a large band.

The tension in Handy’s story reflects the difficult path African American had to walk between the various forms of stereotypes even well-intentioned white people sought to impose, and the aspirations toward respectability and artistic stature of African American artists and intellectuals.

Sources

Adam Gussow, "Make My Getaway": The Blues Lives of Black Minstrels in W. C. Handy's Father of the Blues’ in African American Review, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 5-28

Lynn Abbott and Douglas Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895 (Oxford, MS 2009)

Mario Dunkel, “W. C. Handy, Abbe Niles, and (Auto)biographical Positioning in the Whiteman Era,” in Popular Music and Society, 2015, Vol. 38, No. 2, 122–139

Handy was born in 1873 In Florence, Alabama. His respectable, working-class family recognized his musical ability early, he recalled, but tried to steer him towards religious music, paying for lessons on the organ. Handy however joined a local brass band and concentrated on the cornet and trumpet. He worked semi-professionally as a musician until in the mid 1890s, when he joined “Mahara’s Colored Minstrels,” a touring minstrel show owned and operated by Irish immigrant brothers.

In his autobiography, "Father of the Blues," Handy recalled his pride at being the concertmaster of the band at age 23, able to quickly produce complicated arrangements of any new tune for as many as 42 band members. The successful troupe traveled in style but still had to protect itself against the ever-present dangers of racism. Their rail cars, Handy wrote, had a secret compartment under the floorboard with a stash of weapons, food and clothes in case of emergency. Handy briefly left the Maharas to teach music, then went back to touring with them for a short time in 1903.

Handy’s account of his time with the Maharas is revealing. He described how, when they first arrived in a town, they would parade down main street from the rail station:

In all probability, we would pull the “Musicians’ Strike” out of our bag of tricks. During this well-rehearsed feature each musician would, when his turn came, pretend to quarrel with someone else and quit the band in a huff. When, to the dismay of the innocent yokels, the band had dwindled to almost nothing, a policeman who had been “fixed” and planted at a convenient spot would come up and ask questions. This would lead to a fight between some of the remaining musicians, and the officer would promptly arrest them.

The crowd could be depended on to express its disappointment in strong language. “Just like n——-s,” they’d groan. “They break up everything with a fight. Damn it all, they’d break up Heaven.” During these recriminations we would spring the old hokum. The band, having reassembled around the comer, would cut loose with one of the most sizzling tunes of the day, perhaps Creole Belles, Georgia Camp Meeting, or A Hot Time In the Old Town Tonight, and presently the ticket seller would go to work. Our hokum hooked them.

Handy’s recollection shows the band playing to, and then cleverly subverting, racial stereotypes. in a manner similar to Bert Williams a few years later. The story also suggests his fondness for “hokum” and that we should not take his stories at face value. For example, his famous account of how he first heard the blues at a rural rail station in Tutwiler, Mississippi:

Then one night at Tutwiler, as I nodded in the railroad station while waiting for a train that had been delayed nine hours, life suddenly took me by the shoulder and wakened me with a start. A lean, loose-jointed Negro had commenced plunking a guitar beside me while I slept. His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of the ages. As he played, he pressed a knife on the strings of the guitar in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists who used steel bars. The effect was unforgettable. His song, too, struck me instantly.

Handy’s “lean, loose jointed negro” with his ragged clothes and toes sticking out of his shoes sounds exactly like the stock “Jim Crow” character from minstrel shows, and his reference to playing the guitar “in a manner popularized by Hawaiian guitarists” points out this was not a folk musician Handy heard, but rather a musician familiar with the popular fad for commercial Hawaiian music.

He gave an equally slippery account of his first hit with “blues” in the title, the Memphis Blues.

It was perfectly natural that Pee Wee’s should become the headquarters for our band for a time at least, and in the fall of 1909 I often used to use his cigar stand to write out copies of the following lyric for visiting bands:

Mr. Crump won’t ’low no easy riders here

Mr. Crump won’t ’low no easy riders here

We don’t care what Mr. Crump don’t ’low

We gon’ to bar’1-house anyhow—

Mr. Crump can go and catch hisself some air!

The city was in the midst of a three-cornered campaign to elect a mayor, and our band was beating the drum for Mr. E. H. Crump, who was running on a strict reform platform. I had composed a special campaign tune for this purpose, but without words. We had played it, with success. Meanwhile I had heard various comments from the crowds around us, and even from my own men, which seemed to express their own feelings about reform. Most of these comments had been sung, impromptu, to my music. My lyric was based upon some of these spontaneous comments, with my own development and additions. Luckily for us, Mr. Crump himself didn’t hear us singing these words… Its musical setting, which I afterwards published under the new title “Memphis Blues,” was the first of all the many published “blues,” and it set a new fashion in American popular music and contributed to the rise of jazz, or, if you prefer, swing, and even boogie-woogie.

This story makes no sense at all: the lyrics he describes don’t fit the form of “Memphis Blues” in any way, but do fit the form of a traditional song known as “Mama Don’t Allow.” It positions Handy as a trickster: hired to support Crump’s campaign, he undermines it instead. But he also plays a trick on readers by claiming a relationship between two entirely different tunes. Handy here demonstrates the extremely mixed origins of one of the first blues songs ever recorded. Later, recognizing blues had become a fad, Handy would retitle his song “Yellow Dog Rag” as “Yellow Dog Blues” and watch as sales miraculously increased.

Father of the Blues was written in 1941, late in Handy’s life, when “blues” was well established as genre and when Handy knew that it was popularly understood as an expression of vernacular folk culture, not minstrel shows and political campaign songs. He wrote the autobiography in dialogue with Abbe Niles, a wealthy Wall Street lawyer and jazz enthusiast. Niles wrote music criticism and promoted the value of African American folk music: he pushed Handy to emphasize the folk origins of the blues. Niles wrote the introduction to Father of the Blues, a nickname Handy was happy to accept. At the same time Handy resisted Nile’s efforts to cast him as some sort of musical natural, born with blues in his soul because of his race. He wanted to make it clear he was a professional, capable of composing and scoring complex arrangements for a large band.

The tension in Handy’s story reflects the difficult path African American had to walk between the various forms of stereotypes even well-intentioned white people sought to impose, and the aspirations toward respectability and artistic stature of African American artists and intellectuals.

Sources

Adam Gussow, "Make My Getaway": The Blues Lives of Black Minstrels in W. C. Handy's Father of the Blues’ in African American Review, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 5-28

Lynn Abbott and Douglas Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895 (Oxford, MS 2009)

Mario Dunkel, “W. C. Handy, Abbe Niles, and (Auto)biographical Positioning in the Whiteman Era,” in Popular Music and Society, 2015, Vol. 38, No. 2, 122–139