Vaudeville

Around the middle of the nineteenth century, Americans looking for musical entertainment went to minstrel shows or to mixed performances in what was sometimes called the “variety stage.” Catering to a mostly working class audience, these shows often offended the more delicate sensibilities of the middle class. By the late nineteenth century a new form of organized and franchised stage entertainment, termed “vaudeville,” offered a more family friendly playbill.

Vaudeville was characterized by chains of theaters across the country often bearing the same name in each city. Performers signed a contract with a specific Vaudeville management firm, like “Erlanger” or “Keith,” and then played a “circuit” of Erlanger or Keith-owned theaters in each town. The management firm supplied the theater, drew up a schedule, and settled on a rate of pay. The performer traveled the “circuit” as part of a remarkably varied bill of entertainment that included singers, musicians, jugglers, magicians, blackface comedians, and ethnic comedians of all kinds. A Vaudeville show would mix all these different types of entertainment in a series of “acts.” Many if not all of the most famous singers, dancers and performers of the twentieth century began in Vaudeville, including the Marx Brothers, Jack Benny, Fred Astaire, George M. Cohan, Bob Hope and George Burns.

Vaudeville could be grueling for performers, who had to travel long distances by train and often to perform multiple shows a day. Vaudeville performers had to play for ethnically mixed audiences and subtlety did not pay. Vaudeville music included lots of broad ethnic impersonation and caricature, much of it offensive and belittling, some of it affectionate and kindly meant.

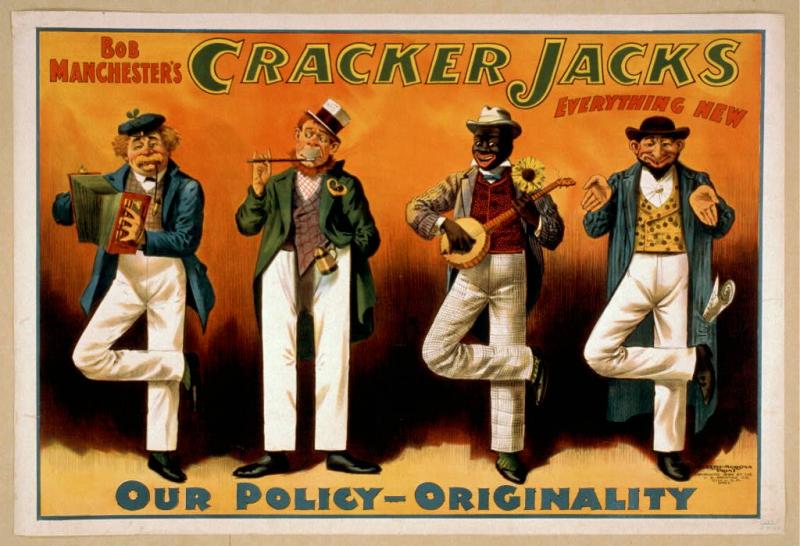

Bob Manchester's Cracker Jacks advertisment

Handbill advertising a vaudeville act, 1899 . Although it promises “originality” it features stereotypes of, from left, German, Irish, African American, and Jewish characters.

The recording industry initially had a very close relationship to Vaudeville, and most of the early recording stars simply performed one of their standard songs or skits for the record.

For example “Uncle Josh” was a common character in Vaudeville: a rustic farmer typically bewildered by nearly every aspect of modern life. In this 1908 recording Cal Stewart performed his “Uncle Josh at the Opera” act.

Or in “Baseball Game,” 1916, Joe Weber and Lew Fields perform a skit about two men with German immigrants trying to understand baseball.

Most of the songs recorded before WWI were intended for the vaudeville circuit. In 1919 Nora Bayes, one of the most popular vaudeville singers of her day, recorded “Prohibition Blues,” a comic lament about the departure of alcohol from the scene. The song is not a “blues” in any recognizable sense but it represents the kind of entertainment vaudeville audiences might have heard as they came to terms with the 18th amendment.

Vaudeville co-existed well with the recording industry: vaudeville stars issued records which made money and promoted the shows. They faced major competition from motion pictures by the 1920s, as movies became longer and better produced. Movies were cheaper to rent and cheaper to show. The 1930s, and the advent of sound in movies, ended vaudeville’s long reign over popular culture.