Habanera

The habanera, a nineteenth-century musical form named for the capital of Cuba, provided one of the most prominent rhythms in twentieth-century popular music

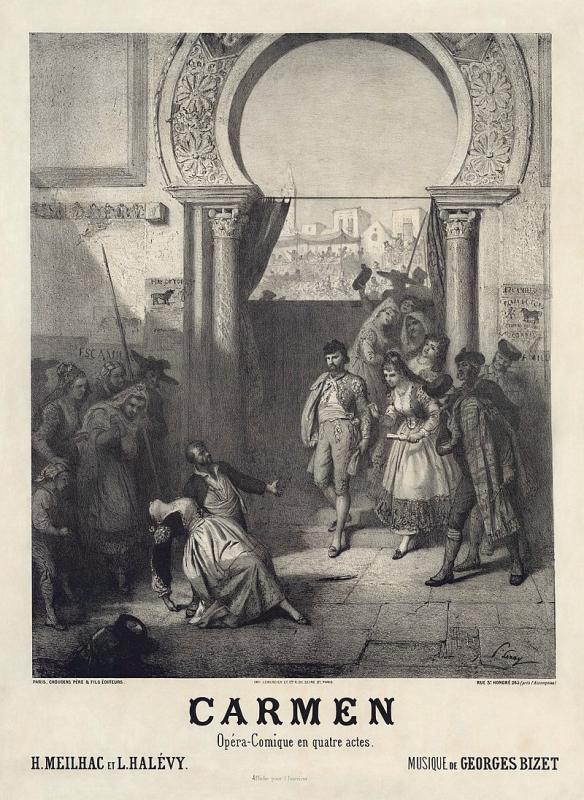

During the mid-nineteenth century, Spanish musical theater companies frequently toured in Cuba, which was still a colony of Spain. In Havana, these visitors picked up a taste for the music of the Cuban danza, itself a local version of the contradance, a dance popular in various versions throughout Europe. These Spanish musicians made the danza a part of their repertoires and brought it back with them to Spain. They called it the habanera in order to emphasize its exotic geographic origin. The music and its associated dance steps were so popular in Spain that when Georges Bizet wrote Carmen in 1875, he included a habanera in order to convey the vibrant popular culture of Seville, where the opera takes place. The famous aria called "Habanera," included here in a 1921 version by contralto Sophie Braslau, features the repeating pulse of the habanera rhythm, which sounds like BUM-ba-dum-bum.

The habanera rhythm would go on to exert enormous influence on music and dance forms throughout the Americas. The tango, and its immediate precursor, the milonga, emerged in late nineteenth-century Buenos Aires and Montevideo as new ways to dance to this rhythm. In the tango "El Pollito," recorded in 1915 by the Orquesta Típica Argentina Celestino, you can hear the the habanera rhythm performed by the piano.

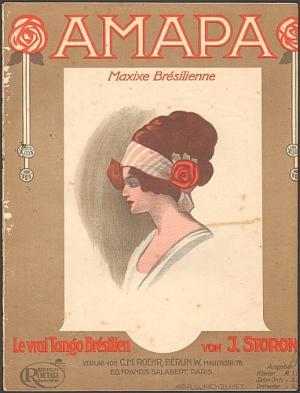

At roughly the same time, the most popular dance for couples in Rio de Janeiro, the maxixe, was also based on the habanera. Both the tango and the maxixe gained a large following in Europe and the United States. In fact, the first record released by the influential New York-based, African-American band leader James Reese Europe featured an Argentine tango on one side (Irresistible) and a Brazilian maxixe on the other (Amapa).

The habanera beat is closely related to two other Cuban syncopations: the tresillo and the cinquillo. The tresillo is a simpler version of the habanera, in which one of the four beats is unplayed. It is sometimes known as "3-3-2," since it can be counted as "1 (2 3) 1 (2 3) 1 (2)." The tresillo figures as one half of the clave, the rhythmic cell that is the basic building block of the Cuban son and of salsa.

The cinquillo is another slight variation of the habanera. It became the dominant rhythmic motif of the danzón, the most popular dance form in early-twentieth-century Cuba. The cinquillo pattern sounds like this (BUM-ba-dum-ba-dum) and can be heard in the danzón, "Los tabaqueros," recorded by the Orquesta de Enrique Peña in 1909.

The danzón was a major influence in nearby New Orleans, where Cuban dance bands toured frequently and where musicians of Spanish Caribbean descent were numerous. When the pioneering pianist Jelly Roll Morton spoke of the "Spanish tinge," which he considered crucial to jazz music, he was referring to these Cuban syncopations. Morton's compositions, "New Orleans Blues" and "The Crave" feature clear tresillo and habanera patterns, respectively, in their bass lines.

Later, the tresillo would provide one of the most common bass patterns in African-American rhythm and blues and, as a result, in such rock and roll songs as Elvis Presley's version of "Hound Dog." These rhythmic forms continue to shape contemporary pop music. The genre of reggaeton, invented in Puerto Rico in the early 1990s on the basis of earlier innovations in Jamaica and Panama, is built on a beat known as dembow that is basically an updated habanera. More broadly, tresillo rhythms continue to feature in dance music throughout the world.