Ethnic Humor

Humor depends on context. Jokes one might tell among friends would be offensive at a funeral. The context of the early twentieth century differs from our own in many ways. Much of the humor in early twentieth-century songs involved making fun of specific ethnic or racial groups, and this humor ranged from good-natured and affectionate to offensively vicious and belittling.

The most notorious examples appear in the minstrel shows, in which white people pretending to be black enacted various comic stereotypes, reinforcing the idea of racial inferiority. Characters like “Jim Crow,” a simple minded, raggedy field hand, appeared on stages everywhere in the US, well into the twentieth century. Minstrel stereotypes are the most common form of what the Library of Congress terms “Ethnic Characterizations.”

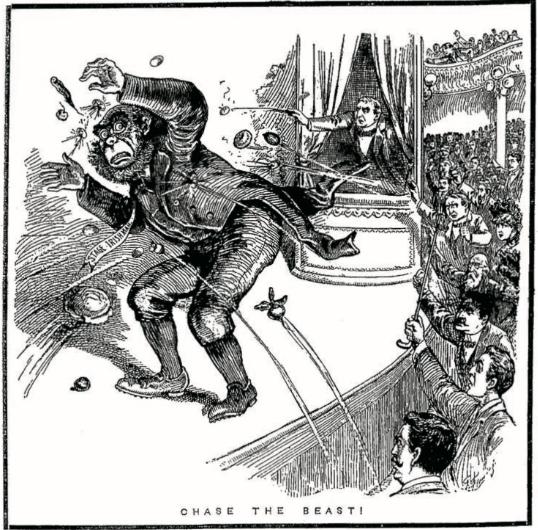

Songs about the Irish are nearly as common. “Paddy,” the “stage Irishman,” played a very similar role to Jim Crow. "The stage Irishman habitually bears the general name of Pat, or Paddy or Teague. He has an atrocious Irish Brogue,” wrote theater historian Maurice Bourgeois, “and never fails to utter...some wild screech or oath of Gaelic origin at every third word....His hair is fiery red: he is rosy-cheeked, massive, and whiskey-loving. His face is one of simian bestiality...In his right hand he brandishes a stout blackthorn or sprig of shillelagh.”

As immigrant groups and their children began to gain political power, they often acted to modify or eliminate the more offensive aspects. By the early twentieth century Irish Amercians began to actively campaign against common stereotypes. For example, the cartoon above asks Irish audiences to chase the “stage Irishman” away.

Similar campaigns by African American and Jewish activists attacked the more extreme versions of stereotyping. A 1910 editorial in the B’nai B’rith News noted “Some time ago a crusade was made against the ‘stage Irishman.’ The colored people have from time to time pro-tested against the ‘stage Negro.’ It concluded ‘‘now we have [to] protest against the ‘stage Jew.’”

Early twentieth century music also commonly mocks Native Americans and Hawaiians, who held less political power at the time and were less able to object. Hawaiian natives did appear in popular recordings, singing in Hawaiian and in English. Native peoples themselves appear much more rarely, but songs built around stereotypes of Native Americans appear often.

In 1902 John Phillip Sousa’s band recorded “Indian War Dance,” with war whoops, percussion, and brass band arrangements of cliche vaguely “indian” melodic phrases. Inexplicably using an Irish accent, vocalist Edward Favor sang “Pocahontas” in 1906.

Ethnic humor often involved imitating one ethnic group in order to make fun of another: people adopting mock Irish accents often sang songs about other ethnic groups.

Several songs combined cliched Hawaiian themes with familiar African American and Irish characterizations. For example, multiple versions of “O’Brien is Tryin’ to Learn to Talk Hawaiian” describe O’Brien’s efforts to woo “Honolulu Loo.” Horace Wright's version, from 1916, includes the playing of the Hawaiian duo Frank Ferara and Helen Louise. Ada Jones recorded "O’Brien is Tryin’ to Learn to Talk Hawaiian” in 1917. This version includes Hawaiian steel guitar.

Ada Jones, born in England and raised in Philadelphia, that same year recorded “Maggie Dooley learned the Hooley Hooley,” in which Irish people have “traded their shillelaghs for ukuleles.”

In “The Germans’ Arrival” from 1906 a German immigrant with a thick accent seeks his girlfriend from the old country but is distracted by the comic yodeling of another German immigrant woman. A few years earlier, in 1903 Collins and Harlan recorded “It was the Dutch,” “Dutch” in this case meaning “German,” as they adopted the same comic accents to extol the virtues of sauerkraut and limburger cheese.

Irish-German rivalry appeared in “It Takes the Irish to Beat the Dutch,” recorded twice by Vaudeville trooper and habitual ethnic faker Billy Murray. Murray, born in the US to Irish immigrant parents, adopts an Irish accent while singing about the superiority of Irish people to Germans.

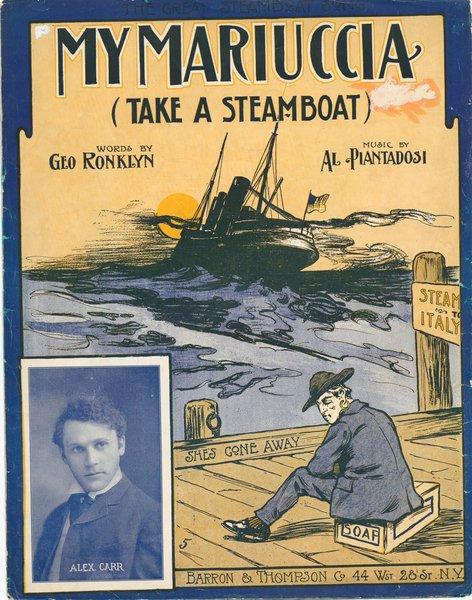

In 1906 Murray, who also sang in blackface, adopted a stereotypical Italian accent to sing “My Mariuccia.” Twelve years later, in 1918, Murray brought out his Italian accent again to sing “When Tony Goes Over the Top,” about an Italian immigrant drafted into WWI.

Multiple recordings include Yiddish or Jewish accents: for example in “Nat’an” recorded in 1916, Jewish singer Rhoda Bernard adopted a heavy accent to sing about how her lover “Nat’an” always kept her waitin’. In “Sheik of Avenue B” Fanny Brice, born in the US to Jewish immigrant parents, adopted a similar accent to sing about a local heartthrob on the lower east side.

Jewish American Irving Kaufman recorded “Chinese Blues” in 1915: the song managed to combine egregious stereotypes of Chinese immigrants with the novel genre”of “blues.”

Though relatively few immigrants of Arab ethnicity lived in the United States before WWI, multiple recordings treat vaguely “arab,” middle eastern or orientalist themes, unhindered by any actual knowledge of middle eastern musical cultures. Billy Murray recorded “Sahara (We'll Soon Be Dry Like You)” in 1920 to lament the coming of Prohibition. Ada Jones in 1909 recorded “Arab Love Song.” And, in 1915, “Down in Bom-Bombay Bay” offers a glimpse of what people who had never been to India and knew nothing of Indian music thought it might sound like.

Much of the ethnic humor of the early twentieth century offends modern ears, because it relies on crude stereotypes and involves “punching down,” making fun of the least powerful and the least able to defend themselves. But it also reflects fondness for immigrants, enthusiasm and pride about the accomplishments of immigrants, and celebrates the diversity of the United States.

For example, two versions of “The Argentines, the Portuguese, and the Greeks” walk listeners through the history of immigration, and the way immigrants appear in every sector of urban life. The song celebrates immigrant financial success and insists immigrants are the true patriots. The Duncan sister’s 1923 version uses the Hawaiian ukulele as accompaniment.