Minstrelsy

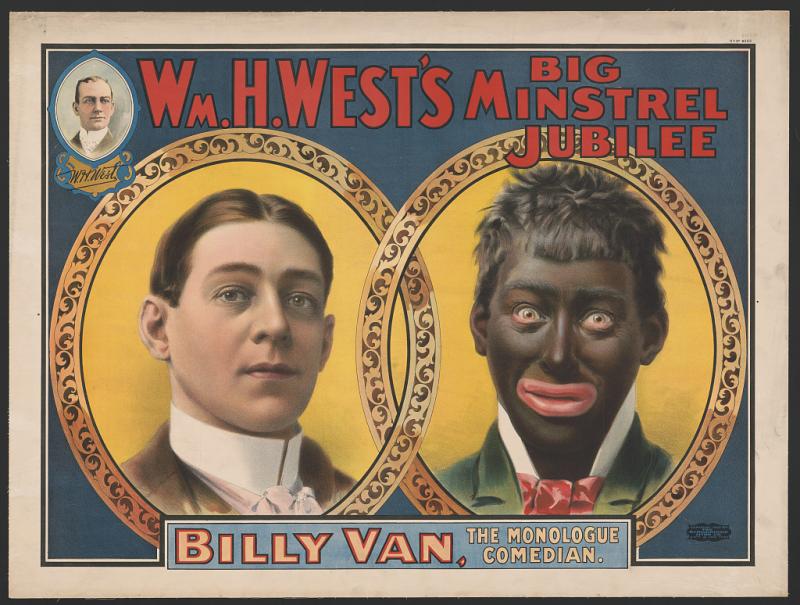

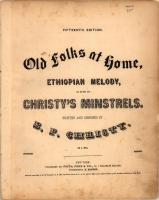

The minstrel show was one of the most complex and troubling phenomena in the history of American culture. In minstrel shows white men “blacked up”: they darkened their faces with greasepaint or burnt cork and acted out various comic characters. Packed with songs, skits, political satire and dancing, minstrels shows were by far the most popular form of entertainment in the US from roughly 1830 into the twentieth century. Virtually all of Stephen Foster's published songs were written for the minstrel stage. “The Yellow Rose of Texas," now the state song of Texas, was a minstrel show song. Similarly “Dixie,” the anthem of the Confederacy, was written for white men pretending to be black. Minstrel troups toured Europe and Latin American to great acclaim: in a very real sense minstrel music was understood as the characteristic music of the United States.

Minstrel shows used racist tropes and caricatures which often portrayed black characters in stereotypically offensive ways. In the earliest minstrel shows, only white people performed on stage. The same basic roles appeared din every minstrels show, for decades: “Jim Crow,” a raggedy, happy go lucky field hand; “Zip Coon,” a flashy character with comic pretensions; “Mr. Tambo,” who played a tambourine; or “Mr. Bones,” who kept time on a pair of rib bones. Minstrel performers often claimed to be presenting realistic versions of African American songs and dances, but the leading composers of minstrel tunes were initially all white men. See for example “I’se Gwine Back to Dixie, recorded by the “Haydn Quartet” in 1906.

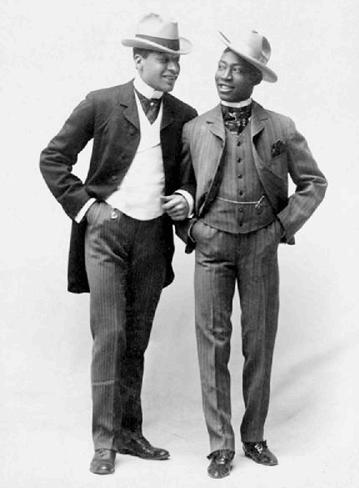

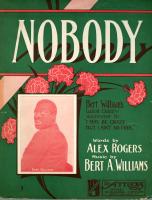

Minstrel shows were popular internationally, in Europe and in Latin America especially. By the 1890s, African Americans had begun to write music for the minstrel show. "Ethiopian Carnival of Melody," from 1902, includes Stephen Foster songs and songs by African American composers. Eventually African Americans themselves begun to appear in “blackface,” with makeup, performing the same kinds of comic stereotypes. Ernest Hogan wrote “I Don’t Like That Face You Wear” in 1895. You can hear minstrel stereotypes performed on record by Bert Williams and George Walker, two of the most famous African American minstrel performers.

Minstrel shows did complex work. Most obviously they reinforced white supremacy. The explicitly racist and often vicious content is unmistakeable. There was no comperable tradition of black people “whiting up” on stage to make fun of white people.

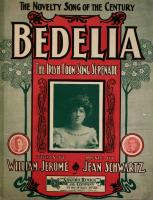

Historians have also suggested that minstrel shows helped ethnic European immigrants to “become white.” The minstrel show cast everything in binary, black and white terms: appearing in blackface called attention to the idea that the performer was “really” white, not Irish or Jewish. It simplified some of the complexities of a ethnically diverse society. Dan Quinn sang “Bill Bailey Won’t You Please Come Home” sometime between 1899-1902. He added exaggerated, comic pitch bends, on "back -yaaaard" and on "the whole day lawoong," that were supposed to signify African American musical practice. But by imitating African Americans, he reinforced the idea that Irish people were unambiguously white. In “Bedelia, the Irish Coon Song Serenade," ethnic, gender and racial catagories mix in slippery ways. But again commercial music did not allow African Americans to perform the same kind of ethnic impostures.

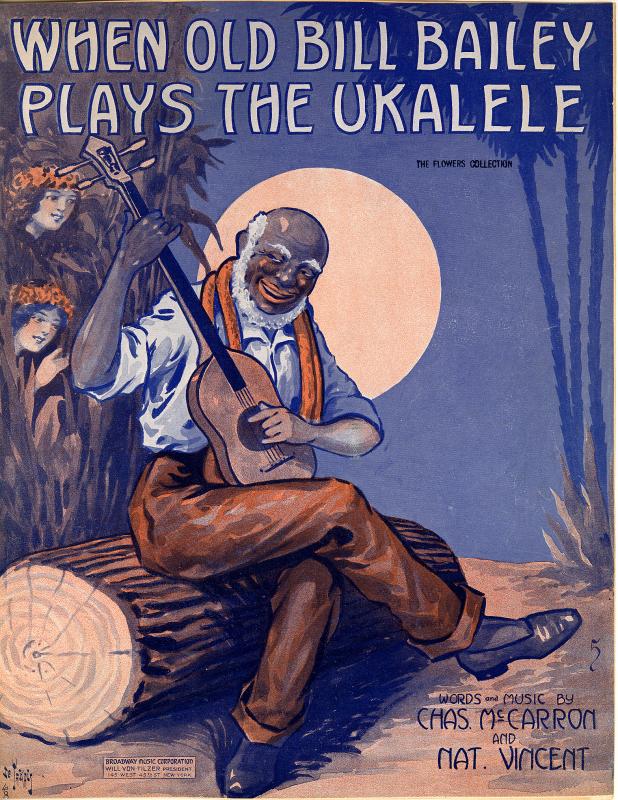

It is difficult to overstate the popularity of minstrelsy. Many of the most famous performers on the early twentieth century—WC Handy, Al Jolson, Sophie Tucker, Bert Williams—appeared in blackface. Minstrel songs, themes, and performance styles show up everywhere in the earliest recorded popular music. For example Nora Bayes, who was born Rachel Goldberg, sang “When Old Bill Bailey Plays the Ukulele” to combine minstrel stereotypes with the growing popularity of Hawaiian music.

The minstrel show's influence appears everywhere. Early jazz recordings regularly featured minstrel songs and even the most ardent fans of Louis Armstrong were dismayed by his willingness to mug for the audience in ways that recalled the minstrel show. W.C. Handy, famous as "the father of the blues," played in minstrel shows for years. Vernon Dalhart, often described as the first singer of country music, abandoned his classical training to sing minstrel songs like "Can't Yo' Heah' Me Callin' Caroline."