Q: Who was the first country singer?

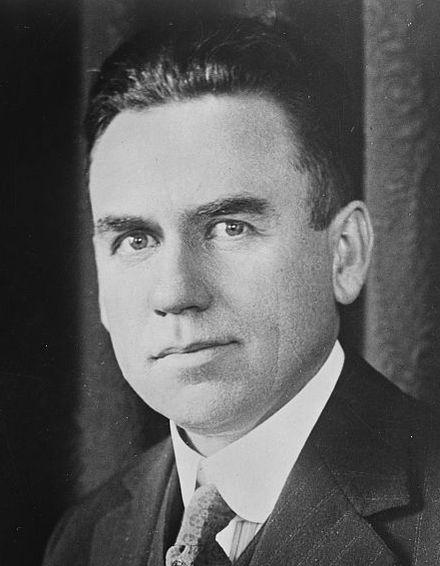

A: Vernon Dalhart.

Born Marion Try Slaughter in Texas in 1883, the classically trained Vernon Dalhart went from singing opera to singing minstrel show tunes to singing “hillbilly” tunes: he could easily be called the first country singer in American history.

Dalhart came to New York around 1910, and initially made a modest living singing opera, but he had more success when he branched into songs where he pretended to be African American. White people imitating black people has a long history in America, a path paved with bricks of cash, and by the 1920s Dalhart was recording more minstrel type songs.

"Can’t You Hear Me Callin’ Caroline," from 1917, is a remarkable recording that combines the formality of a trained opera singer with the cliched fake African American accent adopted by Minstrel and Vaudeville performers. Compare “Can’t You Hear Me Callin’ Caroline” to “Cora,” recorded that same year: Dalhart sings “Cora” straight, with no fake African American dialect.

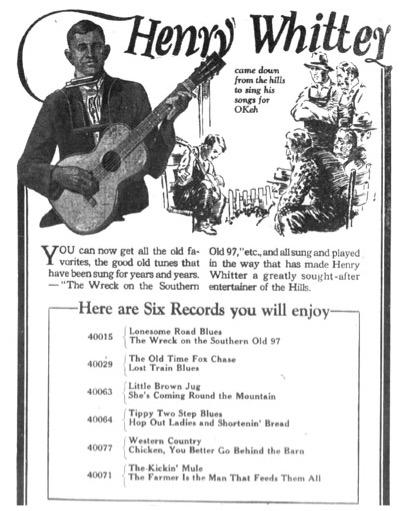

But in 1924 Dalhart made a breakthrough by recording a ballad, called “the Wreck of the Old 97,” in which he adopted the timbre and accents of a rural white man. Versions of the song, based on the true story of a 1903 train wreck in Virginia, had circulated for years. In 1923 Okeh records released an commercially unsuccesful version of the song by Henry Whitter, a Virginian. Record companies had enjoyed success with ethnic recordings, records in foreign languages and/or foreign genres marketed to immigrants in the US. Although Whitter never had much success with this song, Okeh’s executives realized that they could market “old time” music to rural white people in similar ways. Eventually, after 1927, Whitter had found some success in duets with fiddler G. B. Grayson.

Dalhart heard Whitter’s version and decided to do his own. As he had earlier imitated black people, he now imitated Whitter, a white Virginian. The guitar on Dalhart’s recording was played by Frank Ferera, a Hawaiian musician who had made his own recording of Hawaiian songs and Hawaiian-inflected pop tunes. Dalhart’s recording of “The Wreck of the Old 97” is often described as the first record to sell a million copies. The Raleigh, North Carolina, News & Observer claimed “the wreck of the Old 97 is a true ballad--it comes straight from the people," but also noted that “now some ingenious person has made a song about [the wreck] with a crazy jazzy accompaniment.” The Fort Worth Star-Telegram praised his next record, but also pointed out that every railroader already knew that song. Listeners recognized Dalhart’s music as something old but also something new. The unprecendented popularity of the song suggest it can be considered the first Country" single.

Despite his opera training, Dalhart himself positioned his imitations of both African Americans and Henry Whitter as an expression of his roots. About singing in dialect he claimed "Learn it?" he said. "I never had to learn it. When you are born and brought up in the South your only trouble is to talk any other way. All through my childhood that was almost the only talk I ever heard because you know the sure 'nough Southerner talks almost like a Negro, even when he's white. I've broken myself of the habit, more or less, in ordinary conversation, but it still comes pretty easy."

Country music (or “hillbilly” music, as it was called in the 1920s) was born when record companies decided to sell artists like Dalhart as authentic representatives of the musical traditions of poor, rural white people. “The Wreck of the Old 97” presented itself as the voice of white authenticity, but it combined Dalhart’s classical training, and his reputation for “Negro dialect” singing, with Frank Ferrara’s Hawaiian guitar stylings. Country music was a hybridized imitation that came to stand for the things it imitated.

The Dalhart story shows how modern genres like country or blues were formed out of minstrel shows, ethinic recordings, and the intersection of an idea of authenticity with an endless quest for novelty.

Further Reading:

- Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.