Folk Music

The early record companies initially focused on recording vaudeville and minstrel show tunes, classical music, and comic skits, but they would soon come to see the value of “folk music,” a new field of study that emerged in the nineteenth century.

Industrialization and the spread of commercial culture radically disrupted social, political, and intellectual life. Many of these changes were welcome, many were not; but all were jarring and provocative. One response to these disruptions involved a search for alternative realms of human life where people practiced traditional customs and crafts, played traditional music, or told each other stories they learned from family or neighbors rather than from books, records, or theaters. These practices were imagined as separate from commerce. People ostensibly played folk music not to make money, but for their own and the community’s pleasure.

An emerging discipline, “folklore” looked for places where traditions survived. Across the Americas, folklorists sought out people in remote areas, people whose poverty, illiteracy or remoteness insulated them from commercial culture. In Appalachian mountain hollows, Andean and Mexican villages, and Southwestern cowboy saloons, folklorists looked for people on the margins of industrialization and modern life in order to collect and preserve their songs, stories, and crafts.

Folklore privileged “authenticity.” Folklorists wanted to collect songs and musical styles that preserved ancient traditions untainted by modern commercial culture. In the diverse societies of the Americas, this often translated into a search for racial purity: collectors sought authentic survivals of Anglo Saxon, Spanish, indigenous, or African culture.

The person imagined by early folklorists—uncontaminated by modern life, preserved like a living fossil—probably never existed. For example, in the U.S., folklorists continually ran into people who knew old songs that dated back to England in the 17th century, but who also played minstrel show tunes and vaudeville numbers.

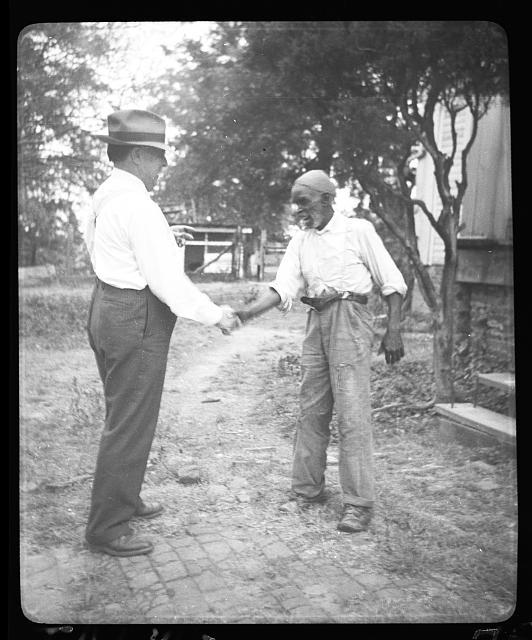

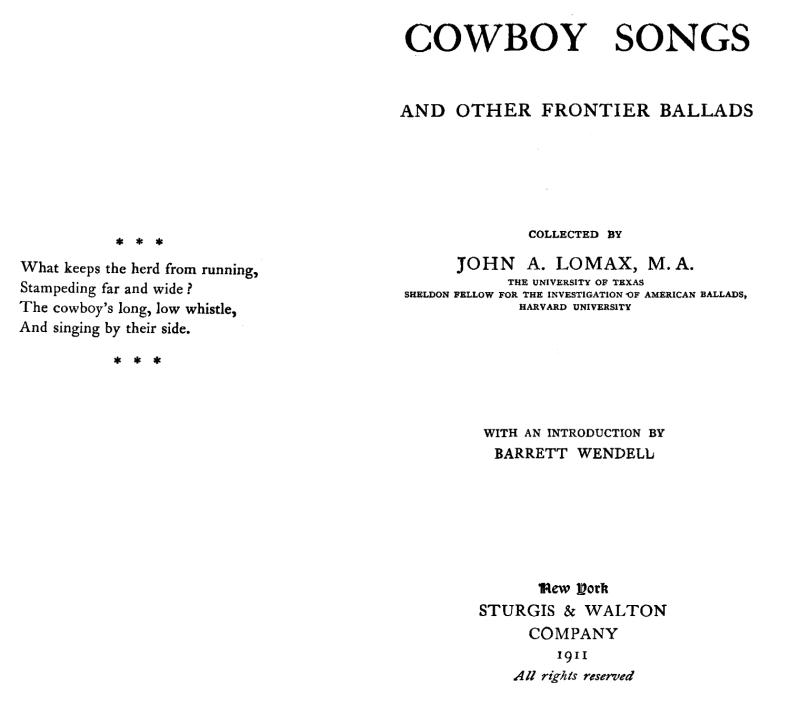

One of the most important North American folklorists was John Lomax, who was raised in Texas and studied at Harvard, and did pioneering work on the collection of “cowboy songs.” In 1910, he published Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, a collection that included “Home on the Range,” which he got from an African American bartender. His book had a forward from Theodore Roosevelt, who himself was very interested in folklore as the record of the Anglo-Saxon race. Lomax’s interest in non-commercial folk culture did not stop him from claiming copyright on the songs.

Like Roosevelt, early Latin American folklorists often looked for evidence of the preservation of ancient European tradition. In the 1920s, Juan Alfonso Carrizo argued that the ballads he collected in Argentina’s Andean northwest preserved the poetry of 17th century Spain. Similarly, the pioneering Mexican folklorist Vicente T. Mendoza traced the corrido and canción ranchera to the Spanish romance and European opera, respectively. For all these folklorists, the stakes were high: they sought to identify the cultural roots of their nations.

The nationalist goals of Latin American folklorists forced them to re-evaluate musical traditions that previously been the target of racist denigration. Scholars like the Cuban Fernando Ortiz and the Brazilian Mário de Andrade explored the musical contributions of people of African descent, developing new theories of cultural mixing to reconcile their admiration of Black music with their dreams of national progress.

The recording industry did not see potential in folk music until the ethnic recording boom of the WWI era. Some of the records marketed as “ethnic music” were, in fact, old songs passed down by oral tradition. In the 1920s, record companies began to apply the ethnic music model to other market segments; if immigrants would buy recordings of their own folk music, perhaps poor whites and African Americans would do the same.

Vernon Dalhart’s 1924 recording of “Wreck of the Old 97” was the first million selling “country” tune. The song itself could be considered a folk song: it tells the story of a wreck in 1903 but draws on a melody at least as old as 1865 and probably older. Dalhart, an educated, classically trained opera singer, cultivated a rural accent to sell his version as “authentic.”

In the 1910s, Black composers like WC Handy and Shelton Brooks depicted their music as authentic, Southern Black culture, even if it was usually performed by whites. Once blues singers like Mamie Smith proved that Black artists could sell records, the record companies sent talent scouts to comb the South looking for “authentic” blues musicians. The music they “discovered” and recorded bore the influence of the folk music paradigm.

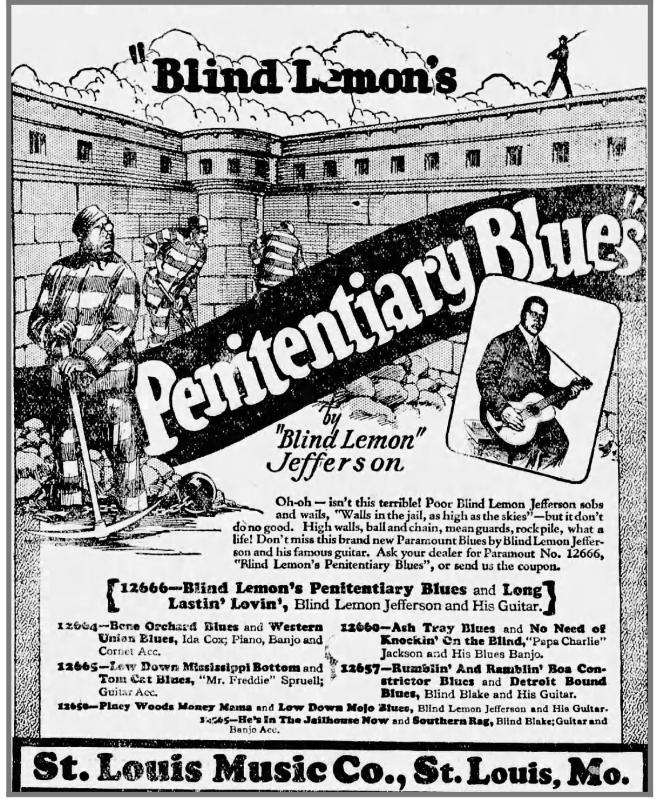

The first “country blues” musician to gain a national audience for his records was the Texan guitarist and singer Blind Lemon Jefferson. Between 1926 and 1929, Jefferson recorded more than 90 songs – almost all of them blues – for the Wisconsin-based Paramount Records label. Jefferson was an innovative musician who played a wide variety of popular styles and who was exposed to the latest fads: in the early 1920s, he was a frequent presence in R.T. Ashford’s record store in Dallas, which sold the latest Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, and Ethel Waters records, alongside records by white artists. Nevertheless, he was marketed as a folk musician. An advertisement in the Chicago Defender for Jefferson’s first record stressed his folk authenticity: "a real old-fashioned blues by a real old-fashioned blues singer... With his singing he plays the guitar in real southern style."

At roughly the same time, musicians in Cuba and Brazil were developing genres that celebrated their own authentic roots in African traditions. Perhaps unlike the blues, both the son and the samba were seen as symbols of the nation. But all these musics were shaped by the ideas disseminated by folklorists.

To learn more:

- Benjamin Filene, Romancing the Folk: Public Memory and American Roots Music (University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

- Oscar Chamosa, The Argentine Folklore Movement: Sugar Elites, Criollo Workers, and the Politics of Cultural Nationalism, 1900–1955 (University of Arizona Press, 2010)

- Alan Govenar, "Blind Lemon Jefferson: The Myth and the Man," Black Music Research Journal 20:1 (Spring 2000), 7-21.

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.