Race Records

For the first twenty years of the recording industry, record companies had little idea what would sell. They were successful with Vaudeville and minstrel songs, songs which were already popular with audiences. Record companies, especially Victor, also had profitable results with classical music, notably with opera singer Enrico Caruso. Although their approach was scattershot and random, they also engaged in a great deal of “training,” explaining in their advertisements how to listen to and use these new technologies. Were records for listening, or for recording yourself? If you listened, did you listen alone or in groups? Did you play a record over and over, or should you play it once and then play something else? How should you store the records or cylinders? Although as with the movies, many people in the record business were immigrants or children of immigrants, they were surprised by the success of “ethnic records” By 1920, record companies had begun to differentiate their product lines by race, inventing a whole new category, “Race Records,” meaning made by and intended for African Americans. If record companies taught their audiences how to listen to records, they also taught them to believe that black and white people played different music.

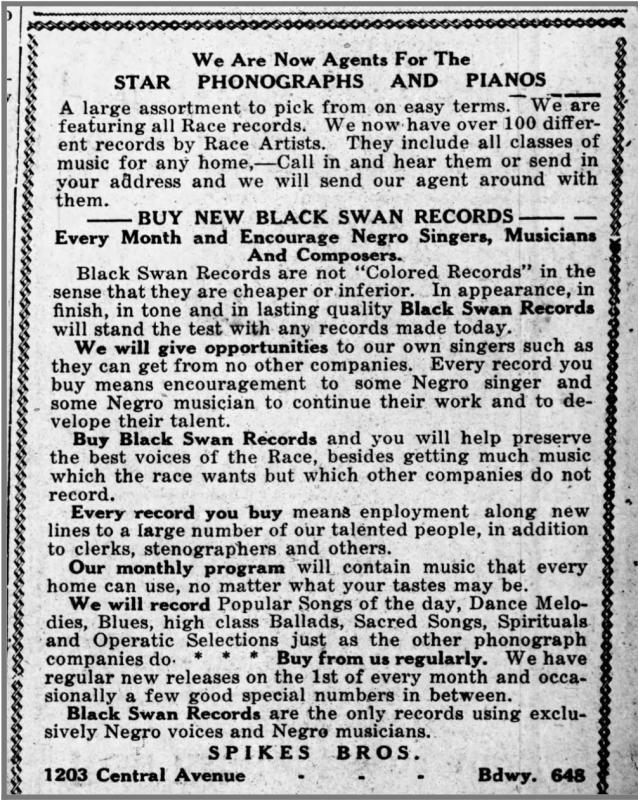

The first race-conscious record company was Black Swan, formed by Harry Pace. Pace was a graduate of Atlanta University, where he studied with W. E. B. DuBois. While working in Memphis on a literary magazine, with DuBois, Pace met W.C Handy. Pace was at that point committed to “racial uplift,” and Handy, a professional musician with a background in minstrelsy, had been frustrated by how the record business handled royalties on his compositions. The two men formed the Pace and Handy music company in 1913 and moved to Harlem, where they were successful publishing sheet music by African American composers. But they disagreed over the potential of records. When they dissolved their partnership Pace formed “Black Swan Records,” the first black owned and operated record company in the US, in 1921. Named after a classically trained African American soprano, Elizabeth Greenfield, known commercially as “the black swan,” Pace’s new record company set out to present the wealth of musical talent in the African American community.

Black Swan’s first recordings were all classical music. Pace wanted to demonstrate that African Americans were as good as anyone at playing the music of European high culture. Those records did not sell well, however, and Pace turned to the popular music of New York. Black Swan found its first big star in Ethel Waters and her recording of “Down Home Blues.” Waters had already sung on the black vaudeville circuit and in carnivals: the record exploited the genre of “blues” Handy had helped establish. At the same time Black Swan marketed it as an example of “jazz,” and listeners will hear the very same sort of“ trombone smears” which originated in the minstrel show and then came to stand for “authentic blues feeling.” Waters went on to have a very long career in American entertainment, while Black Swan turned increasingly toward records marketed as blues and jazz.

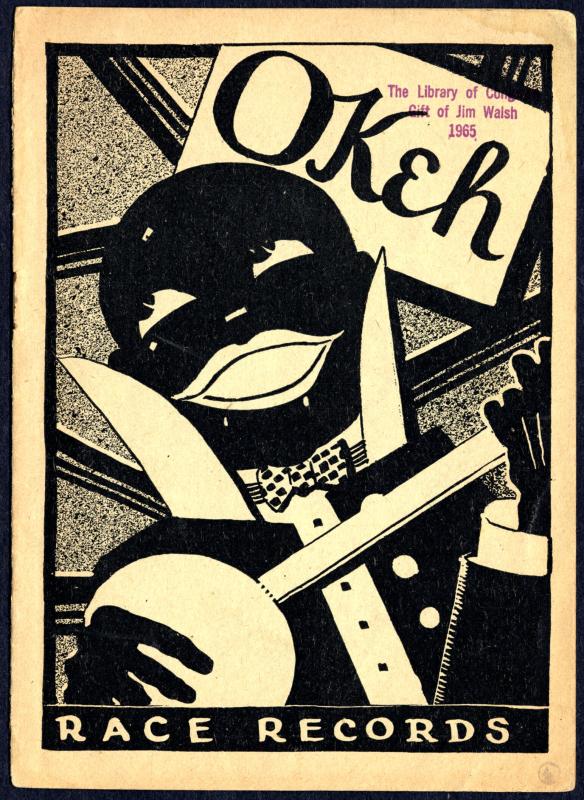

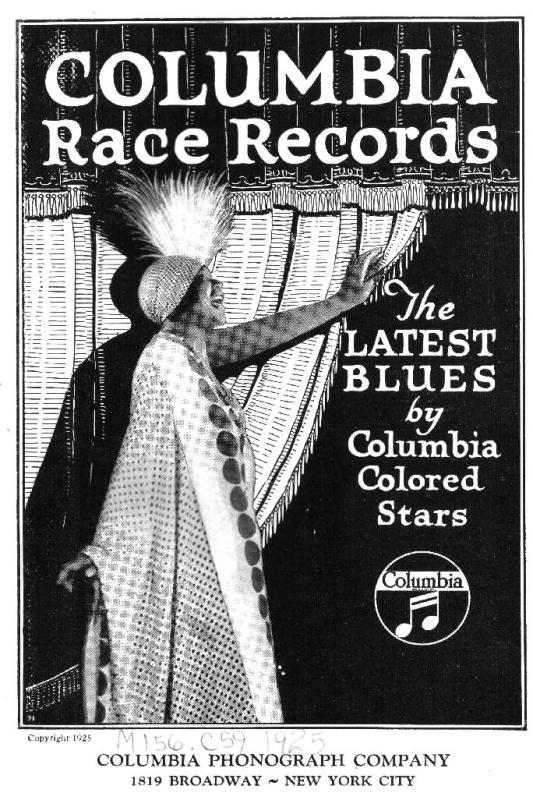

Other record labels noticed Black Swan’s success, and began signing African American artists and forming “race” labels dedicated to music marketed as black. The term “race records” originated with Okeh records. Black Swan ran advertisements claiming that labels like Okeh and Victor were “passing for colored,” signing African American artists while keeping ownership and management in white hands. Pace found it increasingly difficult to compete with record companies that could pay artists more money upfront, and in 1924 he sold Black Swan to Paramount and left the record business.

By then “race records” were an established category, with separate “race music” sales charts. listeners learned to expect that black people to sing and play in one style, and white people in another. But the line between white and black music was never as clear as music marketing made it seem. As Karl Hagstrom Miller has pointed out, in ordinary life black and white Americans listened to many of the same tunes and shared many of the same performance styles. Hearing a song like Henry Thomas, “Railroadin’ Some,” from 1928, modern listeners will have a hard time placing the singer either in terms of race or in terms of genre. Is the song country, or folk, or blues? This is not to say that white and black musical styles were identical: simply to point out that marketing widened and solidified whatever differences existed. Black Swan itself hired several white musicians who it renamed to make them seem like they might be black, including Aileen Stanley, who Black Swan marketed as “Mamie Jones.” At the same time, recordings sold as “race records” by white owned companies often involved white musicians whose presence was concealed. For example Bessie Smith recorded multiple times for Columbia Records with Italian American guitarist Eddie Lang and African American pianist Clarence Williams.

In 1949, Billboard Magazine changed the term “race records” to “rhythm and blues,” at the suggestion of journalist Jerry Wexler. But genre conventions and the segregation of musical styles were by then firmly entrenched.

To learn more:

-

David Robertson, W.C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues (University of Alabama Press, 2011).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.