Q: What did Memphis politician Edward Crump have to do with the blues?

A: He may have inspired W.C. Handy's "Memphis Blues."

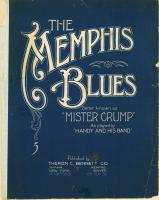

WC Handy wrote “The Memphis Blues” in 1912. It was one of the first songs ever recorded with "blues" in the title. In his autobiography, Handy claimed it originated as a campaign song in support of “Boss” Edward Crump, a Memphis politician. Early sheet music called the tune “the Memphis Blues, or Mr. Crump.” But the lyrics Handy claimed he wrote for "Mr. Crump" don't fit the form of "Memphis Blues." Handy's account is muddled and deliberately confusing

It was also subtitled “a southern rag,” which shows how much “blues” had in common with ragtime. The Victor Marching band recorded this version in 1914, calling it not a blues or a “southern rag” but a “one step.” The stylistic cliches that define blues were just forming.

The song will sound like a ragtime or marching band song to modern listeners. A brass band plays while a drummer articulates snare drum parts on a wooden box. What makes it a blues? For one thing it builds on a “I IV V” pattern. The basic theme includes lots of “blue notes,” notes which add tension because they are in between standard pitches in the major scale. The opening theme starts with Bb, C, Db, D: the Db is a departure from the major scale and causes listeners to want to hear the resolution to D. Similarly the opening theme alternates Gb with G. The Gb is also a departure from the major scale and adds momentary dissonance or tension. These kind of departures were often “bent” or slurred in performance, and this practice of bending or slurring pitches came to be central to what was understood as “the blues.”

In this 1914 version of the Memphis Blues, Vaudeville singer Morton Harvey adds lyrics to the tune. The lyrics were written by a white New Yorker, George Norton, with no input from Handy. They show exactly how confused the meaning of “blues” could be.

Folks I've just been down, down to Memphis town,

That's where the people smile, smile on you all the while.

Hospitality, they were good to me.

I couldn't spend a dime, and had the grandest time.

I went out a dancing with a Tennessee dear,

They had a fellow there named Handy with a band you should hear

And while the white folks gently swayed, all them darkies played real harmony.

I never will forget the tune that Handy called the Memphis Blues.

Oh the Blues.

In this stanza the blues are about urban life and dancing in the South, and express happiness and a welcoming hospitality in the context of segregation, where “darkies” play for white folks.

They've got a fiddler there that always slickens his hair

And folks he sure do pull some bow.

And when the big Bassoon seconds to the Trombones croon.

It moans just like a sinner on Revival Day

These lines associate blues with slick fiddlers, with orchestral bassoons—which were never part of Handy’s band—and trombones, and with tent revivals. The music has gone in a few lines from urban dancing to orchestral music to tent revivals

That melancholy strain, that ever haunting refrain

Is like a darky’s sorrow song.

Here comes the very part that wraps a spell around my heart.

It sets me wild to hear that loving tune again, the Memphis Blues.

Now the song is melancholy and like a “darky's sorrow song,” which makes the singer happy. It’s tempting to see white people’s happiness as related to black people’s unhappiness.

Harvey himself felt the recording failed to capture a “blues quality.” He wrote: “The 'Blues' style of singing and playing, which became so familiar later, was just about to be born. Even the dance records of ‘The Memphis Blues’ made during that period were played as straight one-steps. However, there were a few good old-fashioned "trombone smears" in the orchestral effects of my 'Memphis Blues' record.” Harvey’s comment pointed out that blues and ragtime (the one step) were not then distinct styles. But he also praised the “old fashioned trombone smears,” which locate the blues in comic exaggerations.

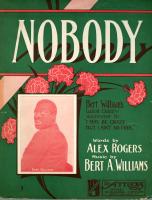

For example, Bert Williams’ wildly popular comic song, “Nobody,” (1903) derived much of its humor from exactly the kind of “trombone smears” Harvey describes as example of blues feeling. “Nobody” was a parody of “sad negro” songs, or what Harvey, above, called “a darky’s sorrow song.” This tradition largely consisted melancholy, nostalgic songs like Stephen Foster's "Old Folks at Home." Multiple times in “Nobody” the trombone makes a long broad “smear” and then Williams imitates it with his voice.

What Williams presented as comedy Harvey saw as authentic. These tragi-comic "trombone smears," repurposed as examples of authenticity, were a central stylistic device in early jazz as well. The Original Dixieland Jazz Band, for example, repeatedly used "trombone smears" like these in their 1921 recording of "Jazz Me Blues."

Indeed the blues as a genre has a such to do with the minstrel stage as it does with field calls and folk music: Handy himself toured as part of “Mehara’s Minstrels” and was proud of their skill and ability to entertain.

To learn more:

- Lynn Abbott and Douglas Seroff, Out of Sight: The Rise of African American Popular Music, 1889-1895 (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2009)

- Mario Dunkel, “W. C. Handy, Abbe Niles, and (Auto)biographical Positioning in the Whiteman Era,” in Popular Music and Society, 2015, Vol. 38, No. 2, 122–139

- Adam Gussow, "'Make My Getaway': The Blues Lives of Black Minstrels in W. C. Handy's Father of the Blues" in African American Review, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Spring, 2001), pp. 5-28

- W. C. (William Christopher) Handy, and Arna Bontemps, Father of the Blues : an Autobiography by W.C. Handy (New York: Collier Books, 1970).

- David Robertson, W. C. Handy The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.