Q: Where do the blues come from?

A: The music business of the 1910s.

The musical genre known as the blues was invented in the early twentieth century. What started as a pop music fad went on to have such an enormous influence that many of the most iconic genres of the twentieth century -- jazz, country, rock and roll -- are inconceivable without it. For decades, scholars and fans have searched for the “authentic” origins of this music. But even if some of the key elements of the blues may derive from ancient folk practices, the genre only emerged when composers, musicians, music publishers and record companies combined these elements with other, more contemporary influences in pursuit of commercial success.

The blues fad erupted in 1912 with the publication of the sheet music for “Memphis Blues” by the African American bandleader W.C. Handy. The song proved enormously popular, and Handy followed it up with “St Louis Blues” (1914), in which he combined this new musical form with another fad of the moment by adding a section in the rhythm of the tango. Sometimes, “blues” was nothing but a marketing label. In 1919, Handy engineered a hit by simply changing the title of one of his earlier songs, “Yellow Dog Rag,” to "Yellow Dog Blues.” "When the popular taste for blues asserted itself," he wrote, “I took out that old number and changed its name.”

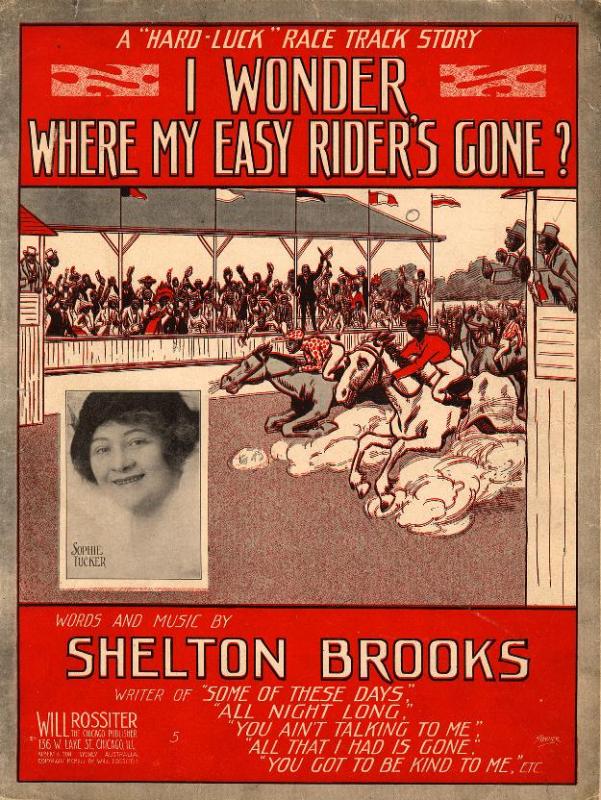

The story of “Yellow Dog Blues” reveals a great deal about the racial dynamics of the commercial popular music of the day. Handy’s song was an answer to “I Wonder Where My Easy Rider’s Gone,” a song about a jockey that the white singing star Sophie Tucker had performed to great success on B.F. Keith’s vaudeville circuit. That song was written by Shelton Brooks, an Afro-Canadian vaudeville performer who composed several of Tucker’s biggest hits, including “Some of These Days” (1910) and “Darktown Strutters’ Ball” (1917). The sheet music cover for “I Wonder Where My Easy Rider’s Gone” included a photograph of Tucker’s white face superimposed on a drawing of a racetrack scene featuring exclusively Black jockeys and fans. In this way, the song was packaged as Black music, ventriloquized by a white singer, and sold to a largely white audience. Like minstrelsy, ragtime, and vaudeville, blues provided Black artists like Brooks and Handy with significant opportunities, but they rarely became stars.

Over the next few years, the blues craze moved quickly from sheet music to records. White singers such as Al Bernard and Marion Harris emerged as specialists in the genre, celebrated for their ability to master “Negro dialect,” while others, like Norah Bayes and Marie Cahill, incorporated blues numbers into a vaudeville repertoire that was already dedicated in large part to ethnic stereotype. Cahill’s recording of “The Dallas Blues” (1917), which opens with a mocking story about an African American poker player, reveals the new fad’s debt to the racist tropes of minstrelsy. Even though it may seem inauthentic in retrospect, the vaudeville blues of this period had a significant influence on the later development of the genre. To cite one example, the “easy rider” of Brooks’s lyric would reappear in countless blues standards, including "C. C. Rider" and "Easy Rider Blues.”

The history of the blues took a significant turn in 1920 when the African American songwriter Perry Bradford convinced the owner of OKeh Records to record the Black vaudeville singer Mamie Smith. The A-side of Smith’s record, “Crazy Blues,” proved surprisingly popular among Black record buyers, opening the floodgates to so-called “race records.” Over the next two decades, virtually every record company followed OKeh’s lead, issuing thousands of recordings by Black artists, largely for the African American market. At first, these blues records sounded quite similar to those recorded by white singers. Many of the first Black blues singers, like we hear in this clip of Mamie Smith, sang in the same polished, urbane diction as their white counterparts, and some songs that had been hits for white singers -- such as Marion Harris’s “I Ain’t Got Nobody” -- were covered by Black singers during the race records era.

But within a few short years, the expectations of the genre had shifted dramatically. African American singers from the South, such as Bessie Smith (no relation), Ida Cox, Sippie Wallace, and Ma Rainey, had come to define the blues singer. Although these “blues queens” dressed in flashy furs and jewels, they sang in an intentionally “down home” style. Listen, for example, to the way Bessie Smith bends the pitch on "too" and "blues." By the mid-1920s, the record companies had decided to go straight to the supposed source, criss-crossing the South and recording primarily male artists who performed a more “country” version of the blues, usually to guitar accompaniment. The advent of race records had transformed blues from a musical form that packaged or represented southern Black culture to one whose performers could be imagined as embodying that culture.

Thus far, we have discussed the evolution of blues as a genre, but what did blues sound like and where did those sounds come from? W.C. Handy’s early blues compositions linked the genre to the twelve-bar, I-IV-V chord progression and the AAB lyric pattern. The blues of the vaudeville era reproduced this format occasionally but not exclusively. During the era of race records, the formula was definitively established. In addition to these formal characteristics, “blues” also came to have certain musical associations, including the powerful emotionalism of singers like Bessie Smith, the tendency to feature so-called “blue notes” -- the flatted fifth and seventh notes of the major scale -- and the use of glissandi (gliding from one pitch to another). Musicologists have located the origins of these techniques in the musical creations of enslaved people, including Christian spirituals and field hollers. They have also traced blues back to Senegambian singing and storytelling traditions, and especially the stringed lutes of this region, which appear to be precursors of the African American banjo.

Nevertheless, these musical elements and approaches were transformed within the arena of commercial popular music. Most contemporary fans developed their ideas about what the authentic, down home music of southern Blacks sounded like not from collective memories of a distant past, but from blackface minstrelsy, which had been selling its own versions of “authentic Black music” since the 1830s. Minstrel acts had established certain forms of syncopation, percussion, and gliding pitches as emblematic of Black musicality. And this commercial culture directly influenced the southern Black blues musicians of the 1920s. Their music was not an ancient tradition preserved by an isolated community.

On the contrary, beginning in the late nineteenth century, the sheet music published on New York’s Tin Pan Alley flooded the South, promoted by the many touring shows that performed in the region; records would soon follow. Southern musicians learned to play “the blues” not from their grandfathers but from these commercial sources. And the South was also not isolated from global trends. During the Hawaiian music boom of the 1910s, dozens of Hawaiian acts featuring steel guitars and ukuleles toured throughout the region. When blues guitar players began to fret their instruments using a bottleneck slide, producing what has become one of the signature sounds of the genre, they said they were playing “Hawaiian style.”

In their everyday lives, the blues musicians of the 1920s played a wide range of different types of music in order to please audiences with cosmopolitan tastes. But once the record companies discovered the commercial appeal of blues, they turned it into a formula; rural, Black musicians were only allowed to record blues. In this way, the race records boom provided opportunities for African American musicians, but it also ghettoized them, limiting them to a style of performance that was understood to be an authentic expression of their race. Many contemporary ideas about what constitutes “Black music” are the legacy of this fundamentally commercial process. The notion that blues is the authentic expression of Black suffering and struggle is one such idea.

The fact that generations of blues musicians—from Bessie Smith to Robert Johnson to Muddy Waters and B.B. King—produced such powerful music within the tight constraints imposed by the genre is a testament not to the authenticity of blues as an expression of a Black musical essence, but to their own artistic genius.

Further reading:

- Daphne A. Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2021)

- Elijah Wald, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues (Amistad, 2012).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.