Music Publishing

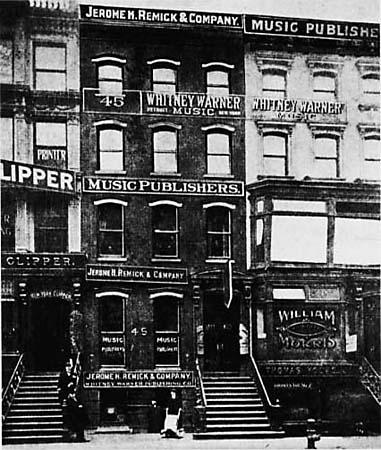

Though the origins of the term are obscure, "Tin Pan Alley" referred to a block of buildings on west 28th street in Manhattan, where music publishers had their offices. Tin Pan Alley thrived as copyright control over music publishing grew more restrictive. Music publishers made their money first through the publication of sheet music, and then later through the ownership of copyrights on recorded songs.

In its heyday from 1890 to 1920 the street echoed to the sound of pianos energetically pounded in dozens of offices by songwriters, salesmen, and "song pluggers" working to convince publishers to accept a new song for publication and recording.

The publishers of Tin Pan Alley exercised tight control over the commercial music market and benefited from a close relationship to the Vaudeville syndicates that dominated American live entertainment. Publishers would send new songs to Vaudeville performers: Vaudeville performers would then sing the new songs as they toured the country, encouraging record and sheet music sales.

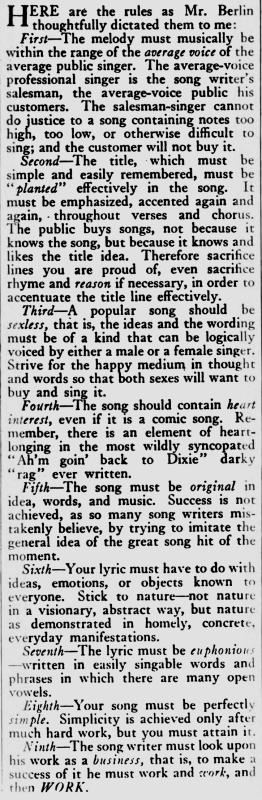

Tin Pan Alley publishers tried to create formulas that would assure sales. In an interview published in American Magazine, October 1920, Irving Berlin gave his "nine rules for songwriters."

Berlin's rules suggest he saw songwriting as an industry churning out reliable product rather than as art.

As Berlin's fourth rule reveals, Tin Pan Alley songwriters adopted styles created by African-American musicians — such as ragtime and blues — in mocking, racist ways. Berlin's own "Alexander's Ragtime Band" is an example. Nevertheless, Black songwriters, such as W.C. Handy and Shelton Brooks, did manage to publish their own music as well. By doing so, they secured their livelihoods and exerted a significant influence over the music business.

Elsewhere in the Americas, musicians and composers of color struggled to secure their intellectual-property rights. Brazilian playwrights and composers organized the Brazilian Society of Theatre Authors (SBAT) in 1917 to enforce their copyrights, but popular musicians, especially Black ones, were poorly represented in the organization. Nevertheless, Black artists recognized that their livelihood depended on their ability to secure their rights as composers.

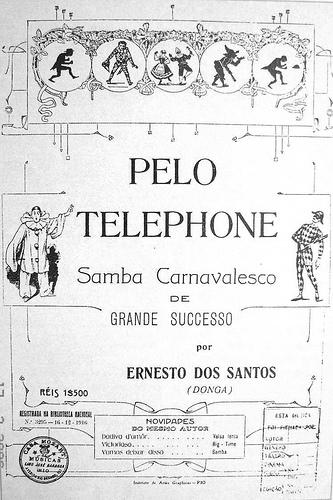

In 1916, an Afro-Brazilian musician named Donga (Ernesto Joaquim Maria dos Santos) registered a song called "Pelo telefone" (On the telephone) at the National Library. Though he gave credit for the lyrics to a white journalist, Donga claimed to have composed the music. Recorded by a singer named Baiano the following year, "Pelo telefone" became a big hit and, crucially, the first hit song to be labeled a samba. In this context, Donga's assertion of intellectual-property rights became controversial: a group of Afro-Brazilian musicians and journalists accused him of stealing the song from others and of selfishly profiting from the work of the larger Black community.

The controversy over "Pelo telefone" reveals both the importance of music publishing to Black musicians and the way that intellectual-property claims could challenge the very idea of "Black music": Was this music the work of individual artists or the product of a community?

Throughout the New World, control of music publishing emerged as a way of shaping and controlling how music was marketed and understood.

To learn more:

- David Suisman, Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music (Harvard University Press, 2012).

- Marc A. Hertzman, Making Samba: A New History of Race and Music in Brazil (Duke University Press, 2013).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.