Q: Who was the King of Ragtime?

A: Scott Joplin, but also Irving Berlin.

Even though Scott Joplin is widely regarded as the most important ragtime composer, and Irving Berlin played no role in the development of the genre, both men were marketed as "the King of Ragtime." This story says a lot about race and the history of musical appropriation.

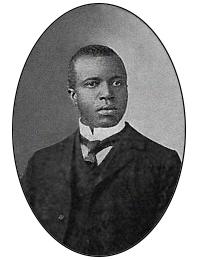

Joplin began writing and publishing music in 1895, right at the beginning of the ragtime craze. In 1899, he published “Maple Leaf Rag,” named for the Maple Leaf Club, an African American dance club in Sedelia, Missouri, where Joplin lived. Joplin had signed a contract with music publisher John Stilwell Stark which guaranteed him a small royalty on sales of his sheet music. “Maple Leaf Rag” became a major hit and arguably the most influential ragtime composition of all time, giving Joplin a modest but steady income for the rest of his life. For the second edition of the sheet music, Stark put a photograph of Joplin on the cover along with the titles of some of his other works. He also included the honorific “King of Ragtime writers.” It’s an assessment that most music historians would agree with.

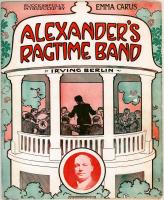

About a decade later, in 1911, Tin Pan Alley songwriter Irving Berlin published “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” which became a massive, international hit and sparked a revival of the ragtime craze. Although the sheet music cover makes the racial identity of the song’s eponymous bandleader ambiguous, the lyrics do not. Alexander was a stock character in minstrel shows, and Berlin peppered the lyrics with idiomatic expressions meant to signal the song’s blackness (“That's just the bestest band what am”). By promising “the Swanee River played in ragtime,” the lyrics referenced the most famous of Stephen Foster’s “plantation melodies,” suggesting a modernized version of a familiar bit of racialized entertainment. The music itself is more Tin Pan Alley pop than ragtime, though it does feature a repeated syncopation intended to remind listeners of the genre.

Berlin reportedly earned more than $1,000,000 in royalties from the song, and the press dubbed him the “King of Ragtime.” For example, the New York Sun labeled Berlin “the ragtime king” and the “Beethoven of syncopation,” celebrating him as a poor Jewish immigrant who achieved success and moved his parents from a lower-East-Side tenement to “a dazzling new house in the Bronx.” Like many immigrants, Berlin used his purported mastery of an African-American musical style in order to Americanize himself.

Berlin’s whiteness certainly made it possible for him to gain fame and fortune as the “king” of a musical genre he had no hand in creating. Joplin, by contrast, tried to move into serious concert music, but failed to find a backer for his opera, "Treemonisha." He went bankrupt, and he died at the age of 48.

In a pattern that would repeat itself over the next decades, white Americans would often claim credit for styles that originated in the African American community.

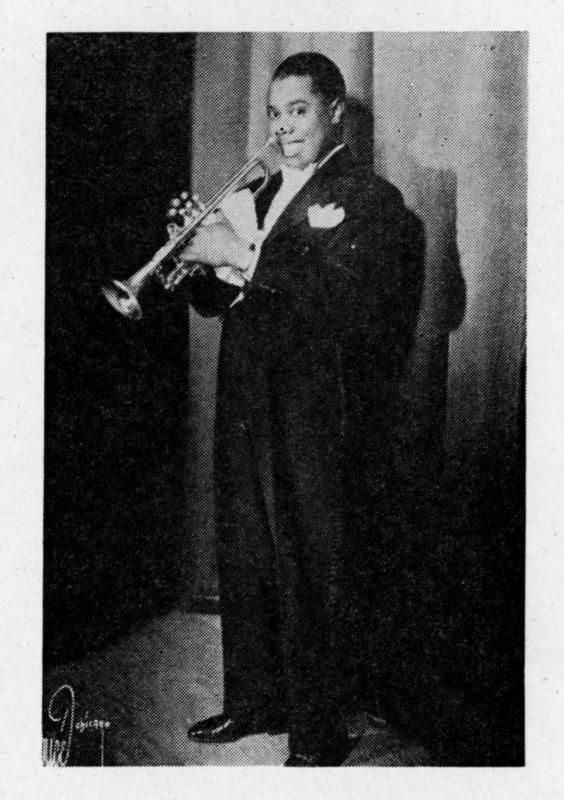

During the 1920s, the New Orleans-born trumpeter Louis Armstrong refined an improvisational, instrumental musical style forged by other Black New Orleanians such as Buddy Bolden and King Oliver. At the same time, Harlem “stride” pianists, such as Fats Waller, James P. Johnson, and Willie “the Lion” Smith, injected a new swinging rhythm into ragtime, and bandleaders like Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington dramatically transformed what a dance band could sound like. Together, these developments created jazz. White musicians also played jazz in these early years, but music historians tend to agree that African American musicians deserve the credit for most of the major, early innovations in the genre.

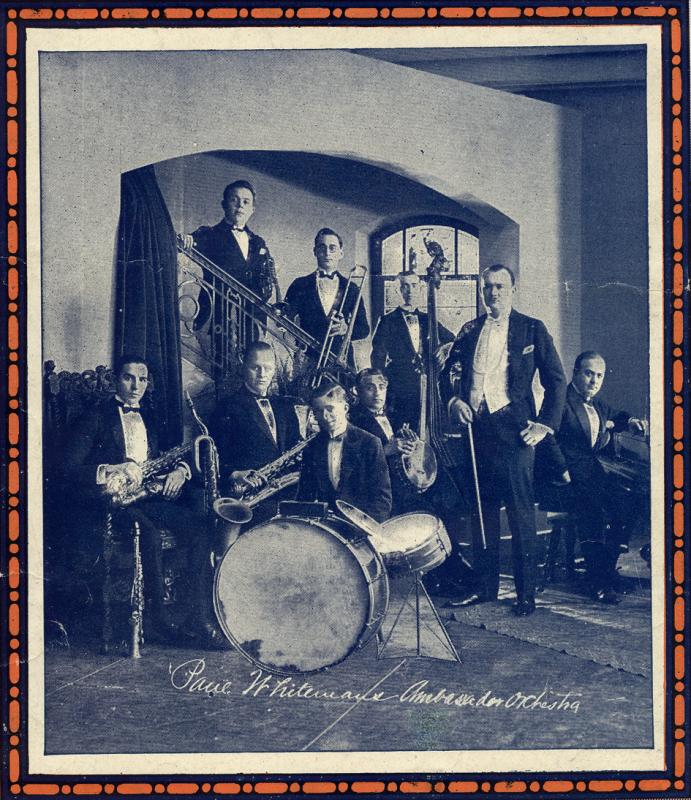

Yet once again, a white man managed to position himself to take the credit. The aptly named bandleader Paul Whiteman recorded “Whispering” for Victor in 1920. The song was a massive hit, and though it doesn’t sound much like jazz to modern ears, it launched Whiteman on the path to proclaiming himself the “King of Jazz.” During the 1920s and early 1930s, Whiteman was the most prominent jazz musician in the world. His so-called “symphonic jazz” made an unruly form of Black music safe for white consumption. By orchestrating jazz, Whiteman claimed to lift it up from its disreputable beginnings.

But the story of jazz ends differently than the story of ragtime. Giants like Armstrong and Ellington did not have to wait until after their deaths to be recognized as the architects of jazz. Already in the mid 1920s, white critics such as Edward “Abbe” Niles declared that the “hot jazz” played by African American musicians was more authentic (and better) than the “sweet jazz” played by Whiteman and other white bandleaders. We might find this claim of racial authenticity problematic since it suggests that Black people have a natural gift for jazz, but it helped Black innovators achieve stature among white jazz fans.

To learn more:

- Charles Hiroshi Garrett, Struggling to Define a Nation: American Music and the Twentieth Century (University of California Press, 2008).

-

Mario Dunkel, "W. C. Handy, Abbe Niles, and (Auto)biographical Positioning in the Whiteman Era," Popular Music and Society 38:2 (2015), 122-39.

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.