African-American Theater Circuits

As sound recording technology developed in the first few decades of the twentieth century--moving from scientific invention to working-class novelty to a central feature in the middle-class parlor--the music industry offered performers new opportunities. However, recording technology continued to co-exist with older forms of media, such as sheet music and vaudeville shows. In fact, the stage remained one of the most effective advertising and distribution tools for early recording companies and their stars.

Apart from a handful of successful Black recording artists, record companies largely neglected Black performers and consumers in the early decades of the industry. Many early recordings featured racial and ethnic stereotypes, but companies typically hired white performers who adapted minstrel and vaudeville performance into a new kind of sonic blackface on record. The continued popularity of blackface in the recording industry meant that when Black performers did get hired to make a record, they were typically hired to perform "coon" songs or other forms of racist comedy.

This complex blend of musical talent, comedic performance, and racist stereotype continued to define most entertainment opportunities available to Black performers at the beginning of the twentieth century. Within this context, theater circuits operated as a lucrative part of the touring landscape of the early twentieth century for the hundreds of Black performers who did not make it to record. Signing a contract with a theater circuit provided an artist or touring company automatic access to a network of partner theaters, increasing the potential profit to be made during a touring season. It also provided some protection for Black performers from potentially abusive practices at the hands of independent theater owners.

In addition to theater circuits, many Black artists performed in more rural areas as part of itinerant tent shows. These were elaborate productions, with touring companies often announcing their arrival in each new town with brass bands, sporting matches with local residents, and smaller performances before the main event. From the stages of the tents and theaters in these touring circuits, Black peformers seized the limited opportunities available to them within the entertainment industry and continued to shape the cultural, political, and musical life of America.

Tri-State Circuit

While the recording industry centralized around a few major labels in urban, Northeastern cities, theater circuits provided an opportunity for performers to tour in theaters across the nation. Early Black theater circuits developed in regional networks primarily led by non-Black managers. For example, Italian immigrant Fred A. Barrasso organized the Tri-State Circuit in 1910. Drawing from the established popularity of tented minstrel shows in the South, the Tri-State circuit brought a more refined style of Black vaudeville performance to Southern theaters. Headquartered in Jackson, Mississippi, Barrasso’s artists traveled to Southern theaters throughout Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas.

Touring shows featured all the elements of Black commercial musical performance of the time, including “coon” songs and minstrel performances as well as comedic and acrobatic acts. However, touring circuits also helped to popularize new musical styles associated with Black performers. For example, W.C. Handy published the first commercial blues song in 1912 called “The Memphis Blues, which was recorded two years later due to its initial success. The Tri-State Circuit featured Black performers like future "blues queens" Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, who would become recording stars in this new genre during the 1920s.

Theater circuits provided economic opportunity for Black performers during a time when most Black Americans worked in service or agricultural labor. On the stage, whether playing into racial sterotypes popularized by minstrelsy or performing new styles like blues, performers like Smith and Rainey were professionals in an industry that provided them entry into the growing Black middle class.

Even for the most successful performers, the volume of performances in a theater circuit often led to grueling touring schedules. Touring companies traveled from city to city in rail cars filled with musicians, singers, dancers, comics, and work crews. Racism continued to structure the entertainment industry, and Black vaudeville performers regularly faced issues in travel, pay, and treatment that their white counterparts did not.

In the South, touring schedules often followed the rhythms of agricultural labor, bringing popular acts to audiences near laboring camps across various industries, although the most lucrative time of year was during the fall cotton harvest in the Mississippi Delta. So, although many Black performers in these circuits used their talent to escape manual labor, these tours kept them connected to the seasonal rhythms that structured agricultural labor. This also allowed less commercially viable forms of Black music making like rural blues to continue developing in tents and theaters across the South. The record industry would not start recording these styles of music until the 1920s, but perfomers honed their talent on circuit stages long before making their first record.

S.H. Dudley Circuit

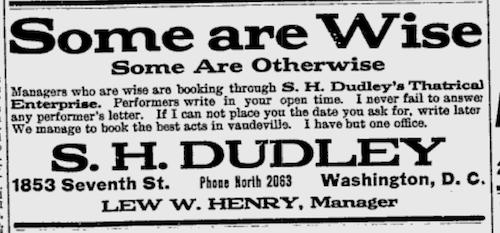

Primarily white bookers and theater owners ran Black theater circuits, reinforcing the color line that structure American society and the entertainment industry. A notable exception to this dynamic is the Black owned and operated circuit run by Sherman H. Dudley. Born in the 1870s in Dallas, Texas, Dudley became a successful performer in his own right. Like many Black performers of the time, he primarily wrote and recorded "coon" songs which drew on racial stereotypes largely derived in minstrel shows for comedic effect. In 1904, Dudley became the star and later the director of the popular Black traveling vaudeville company the Smart Set until 1912, when he shifted his focus toward his own theater circuit.

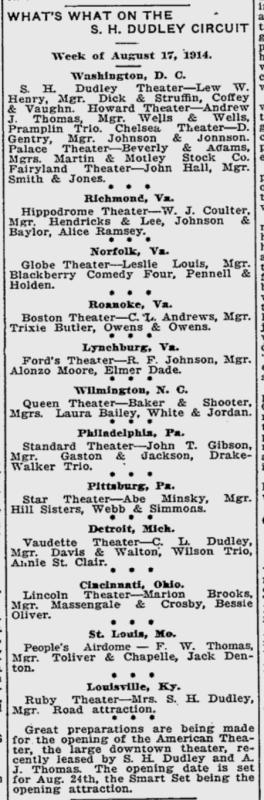

Dudley leveraged his own noteriety as a vaudeville star to improve the commercial potentials and conditions for all Black performers in the entertainment industry. In Washington, D.C., he became the manager and treasurer of the Colored Actors' Union. In 1911, he established his circuit as the S. H. Dudley Theatrical Enterprises, which became known as the "Dudley Circuit" and was regularly publicized in Black newspapers like the widely-read Indianapolis Freeman. At its peak, the Dudley Circuit gave many notable Black performers access to over twenty theaters across the North, South, and Midwest. For example, Mamie Smith performed on the Dudley Circuit before recording "Crazy Blues" in 1920, which became the first hit blues record and began to demonstrate to recording companies the potential of Black women as both performers and consumers. As his circuit continued to grow, Dudley advocated for black artists pay and treatment, and was generally seen as a positive figure in the Black Press. Eventually, Dudley expanded his circuit to over fifty theaters by consolidating with other bookers and theater owners and provided even longer seasons for Black artists.

Theater Owners' Booking Association

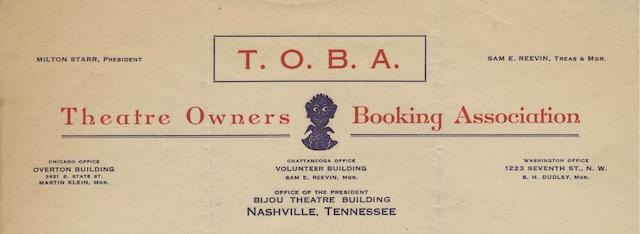

In 1921, the era of regional, independent circuits ended with the announcement of the Theater Owners Booking Association, or T.O.B.A. This new circuit consolidated over a hundred theaters across the nation at its peak, including those part of the former S.H. Dudley circuit who served on its Board of Directors. This created a virtual monopoloy over the Black theater circuit business and extended Black performers' ability to assert their artistry, professionalism, and popularity through a longer touring season and increased potential for profit.

T.O.B.A. also demonstrated the widespread popularity of new musical styles like blues to recording companies, which helped to encourage the race records industry that began to develop in the 1920s. Ultimately, the double impact of the Great Depression and the rise of film forced the decline of T.O.B.A. However, for many decades some of the best Black talent toured on this circuit including familiar acts like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith as well as musicians like King Olivier and Louis Armstrong, a young Count Basie, and an even younger Sammy Davis, Jr.

The legacy of performance on Black theater circuits goes beyond the content of each show or the recording genres they inspired. Traveling could be a harrowing experience for Black performers who faced the constant threat of racist violence and discrimination on the road. However, touring also kept them connected to the 90% of African Americans who still lived and worked in the South. Within the tent or theater, Black performers used their talent and creativity to create a space, particualrly for Black audiences, to critique racism and reinvent racist forms of entertainment rooted in blackface minstrelsy. Despite the restricted opportunities in the entertainment industry, then, Black performers used the stage to assert racial dignity, economic advancement, and political equality for all Black Americans.

On record, we can hear the voices of a handful of the most commercially successful Black theater circuit performers, such as Mamie Smith or Jelly Roll Morton. However, buried beneath these recorded performances are hundreds of other voices that never made it to record but impacted the development of American entertainment all the same. One such performer is Butler “String Beans” May, who was considered one of the most popular Black performers of the 1900s and 1910s. Despite his popularity on touring circuits and his wide coverage in the Black press, he is rarely acknowledged for his artistic contributions due to his absence from the archive of recorded sound. May died in 1917, before his more rural version of the blues became popularized on record, but had a huge impact on other contemporary performers and the development of the blues as we hear it today.

So, when listening to early recordings, we must remember to situate these sounds within the larger chorus of Black performers whose voices never made it from the stage to the record, yet influenced the cultural, musical, and political landscape of 20th century America.

Further Reading:

- Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff, Ragged but Right: Black Traveling Shows, “Coon Songs,” and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2012).

- Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

- Athelia Knight, “He Paved the Way for T. O. B. A.” The Black Perspective in Music 15, no. 2 (1987): 153–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/1214675.

- Karen Sotiropoulos, Staging Race : Black Performers in Turn of the Century America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.