Q: What was the most popular kind of band in America and worldwide in 1900?

A: The brass band.

Many of the recordings from the early twentieth century involve brass or “military” bands, and modern listeners might find it strange to hear blues or ragtime played by what sounds more or less like a marching band. For example the “Victor Military Band” recorded the “Joe Turner Blues” medley in 1916. Because of the limits of early recording technology, the drummer played a woodblock instead of a snare drum.

The early recordings give us a clear look at one of the most common ways ordinary people experienced music.

Brass bands once played a large role in nearly all American communities, as well as in Europe and Latin America. A combination of social club and public entertainment, brass bands wore uniforms, paraded on festive occasions, and entertained the community in parks and streets. Many brass bands formed out of experiences citizens had in the military, and the schooling musicians received in the military bands filtered into other popular forms.

In the US, for example, minstrel performer Dan Emmett, famous as the composer of “Dixie,” got his start in military bands, where he learned to read and write music fluently. By the 1850s, "all at once," complained Boston music critic John Sullivan Dwight, "the idea of a Brass Band shot forth: and from this prolific germ sprang up a multitude of its kind in every part of the land, like the crop of iron men from the infernal seed of the dragon's teeth."

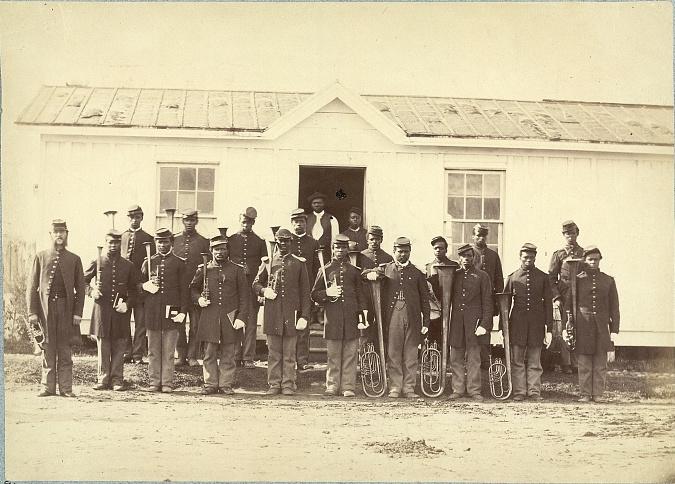

Civil War recruiters used brass bands to attract potential soldiers and build morale. “At the beginning of the war every regiment . . . had full brass bands, some of them numbering as high as fifty pieces,” wrote bandleader Frank Rauscher. The Army, then segregated, had separate “colored” regimental bands.

Immigrants from Italy, Ireland, Germany, England, and Latin America brought their own brass band traditions to both rural and urban communities in the United States. John Phillip Sousa, one of the most famous American composers, was the son of a German mother and a Portuguese immigrant father who played trombone in the US Marine Band. Sousa joined the band himself as a very young boy. Sousa’s famous marches would be a major part of the repertoire of brass bands across the country. You can hear Sousa’s band playing the “El Capitan March” sometime between 1901 and 1904.

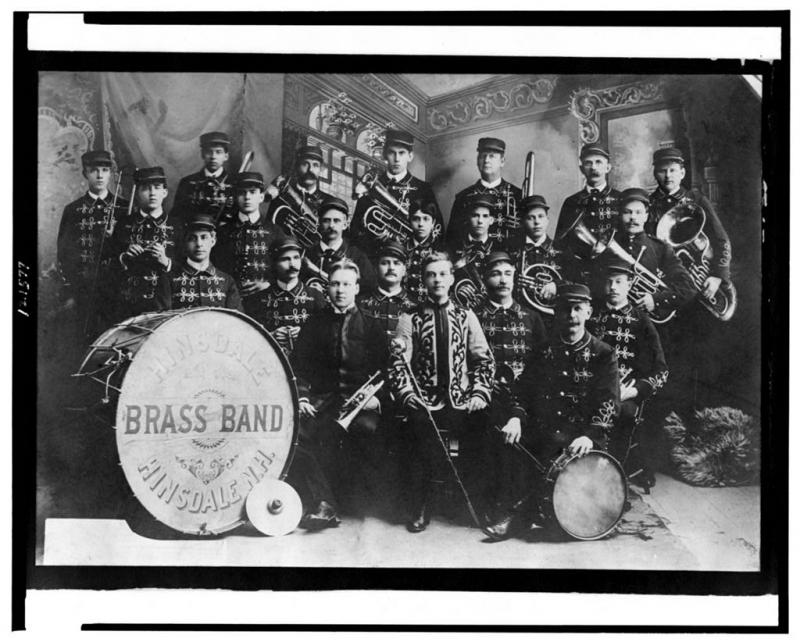

Brass bands ranged from local amateur organizations to professional bands hired for formal occasions. Circuses and minstrel troupes would travel by train with uniforms and brass, and on arriving in a new town would parade down main street to “drum up” ticket sales. Colleges formed brass bands. Small towns typically had bandstands where local brass bands would perform or compete against each other.

When the era of recording began, professional brass band musicians offered record companies a familiar sound and skill at reading music. Local brass bands could compare themselves to a professional band or use the record as the basis for their own performance. Unlike the more formal orchestras, brass bands could play a range of music, from “classical” pieces to syncopated music designed to set toes tapping in a parade.

In this 1901 example you can hear Sousa’s band play “A Coon Band Contest,” in which the band tries its hand at a ragtime feel, with a comic trombone slur. Before the Civil War the term "coon" referred to a kind of slick, smart rural or frontier person: Davy Crockett would call himself a "coon." By the 1890s, the word had become a racial slur used to describe African Americans, and also a genre of music inflected by Ragtime.

In this 1915 example, the Victor Military Band plays a medley of minstrel show tunes.

African Americans like James Reese Europe recorded with brass bands, often adding banjos as would have been heard in minstrel show parade bands or on dance floors. His 369th Infantry Regimental band, nicknamed “the Harlem Hellfighters,” wowed the French with its combination of military precision, virtuosity, and “ragtime” style, derived from Europe’s career leading the Society orchestra of dancers Vernon and Irene Castle. Europe’s band also included a large number of musicians recruited from Puerto Rico, which had its own tradition of brass bands.

Here Europe’s band plays “Missouri Blues” in 1919. The ornate arrangment and ragtime syncopation will probably not conform to a modern person's sense of what blues is supposed to sound like.

When we hear the brass or “military” band on these early recordings, we should hear them in the context of community music making and civic pride as well as lively commercial entertainments.

To learn more:

- Margaret Hindle Hazen, and Robert M. Hazen. The Music Men : an Illustrated History of Brass Bands in America, 1800-1920. Washington, D.C: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987. Print.

- Ned Mark Hosler, “The Brass Band Movement in North America: A Survey of Brass Bands in the United States and Canada.” ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1992.

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.