Ragtime

“Ragtime” was both a musical style and a kind of cultural fad or craze. It referred to a specific kind of syncopation that people heard as more loose or “ragged” than march music. It tended to emphasize or accent beat 2 and 4 while march music tended to emphasize beats 1 and 3, but “ragtime” also added a tendency to accent notes unevenly and in unexpected ways, and so it also stood for modernity, sophistication and surprise.

Like most American music, Ragtime was racially “coded.” Originating in the African American community, particularly in the Southwest, it drew on earlier African American variations on march music and also on music played at minstrel shows and “cakewalks.” It had roots in popular culture and branches that reached, in the hands of composers like Scott Joplin and Tom Turpin, towards opera and art music. Ragtime quickly became a national craze, and as a popular fad it expressed energy, youth, excitement and the busy rush of modern life. Ragtime was also closely associated with forms of dancing, like the Foxtrot or the One Step, that often began in working class neighborhoods but became respectable as they spread to the middle and upper classes.

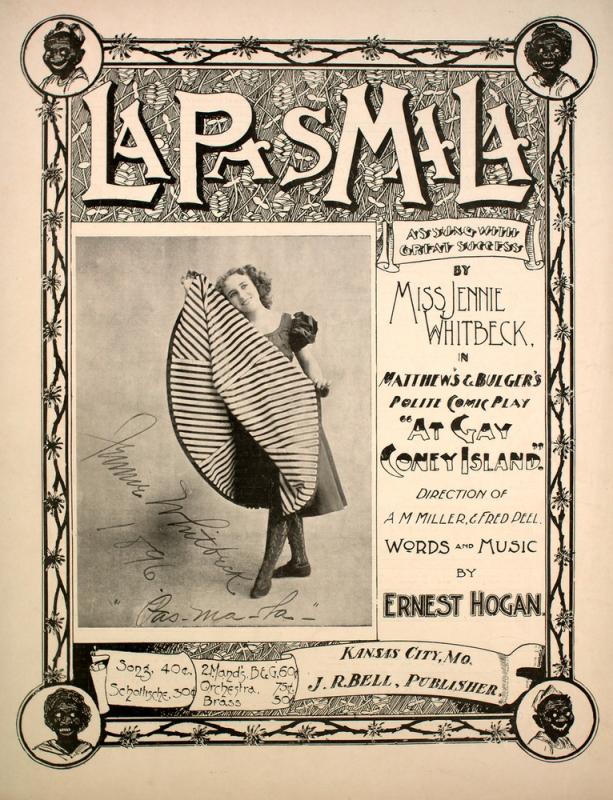

Eventually “ragging” tunes—adding uneven syncopations—became a common trick and a cliche. African American Vaudeville performer Ernest Hogan is often identified as one of the originators of “ragtime” for his songs “La Pas Ma La” and “All Coons Look Alike to Me” (a title he would eventually repudiate). “Ragging” eventually contributed to the development of jazz and swing. The ragtime genre included formal composers like Scott Joplin and also pop composers like Irving Berlin, whose song “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” bore only a passing resemblance to ragtime.

These short examples use the familiar Scott Joplin tune “The Entertainer” to show the idea of “ragging”. First, you can hear the song played as Joplin wrote it . Here, the melody is played without syncopation. The first Joplin version is unevenly accented, or “ragged,” which gives it rhythmic drive.

The following song, Tom Turpin's "St. Louis Rag" published as sheet music in 1903, shows some of the forms ragtime took. This composition by Turpin is a classic in style. It was written for the St. Louis World’s Fair of 1904. Turpin accents the 2 and 4 of the beat. Listen at five seconds where the introduction ends and the piano starts:

Bass chord bass chord

1 2 3 4

The introduction you heard is itself “ragged,” in that it’s unevenly accented.

The next song, “Ragging the Scale" recorded by Conway’s Band in 1915, makes clear what “ragging” meant in popular culture. The melody is built on a major scale, but instead of being evenly accented—do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do—it syncopates the scale in kind of a galloping feel: Bum ba Dum ba Dum ba Dum.

To make the distinction clear, at several points the song also plays the major scale "straight," not “ragged." The musical surprise in the song comes from an expected form, the evenly accented major scale, being syncopated.

Nora Bayes was a very popular vaudeville performer. In her 1917 recording of “Ragging the Songs Mother Used to Sing," she describes how Ragtime has overtaken sentimental traditions. The title references a sentimental Irish ballad, “Songs My Mother Used to Sing,” but suggests mother sings in a ragtime style now. The lyrics mention tango and ukeleles -- popular fads from South America and Hawaii -- in order to link “ragging the tune” with the latest in popular culture.

There are multiple references to other songs. For example, this arrangement quotes “Ragging the Scale” at 29 seconds. The song also twice quotes in a teasing way from the opening stanza of “Silver Threads Among the Gold,” a popular sentimental song of the time. In the lyrics of this song, we can see how “ragtime” stands in for modernity and change, with an element of exoticism:

When I was a child

My mother often smiled

When my eyes would beam with joy

As she sang her songs to me

The way she sings them now

Is different, I’ll allow

She even rags the scale, and all those melodies

The star spangled banner

She sings in a manner

That makes you want to throw your shoulders in the air

All the neighbors declare that she is there

She’s a bear

Why every day at three

She comes and looks for me

And then says take me to some good old tango tea

And then they rag the songs my mother used to sing to me

When as a child she used to bounce me on her knee

Those good old melodies are hard to beat

And even now she sings them

So soft and sweetly

Darling I am growing older, and bolder

Oh sing for me an old time melody

And then we hear those ukuleles full of harmony

As they rag the songs my mother sang to me

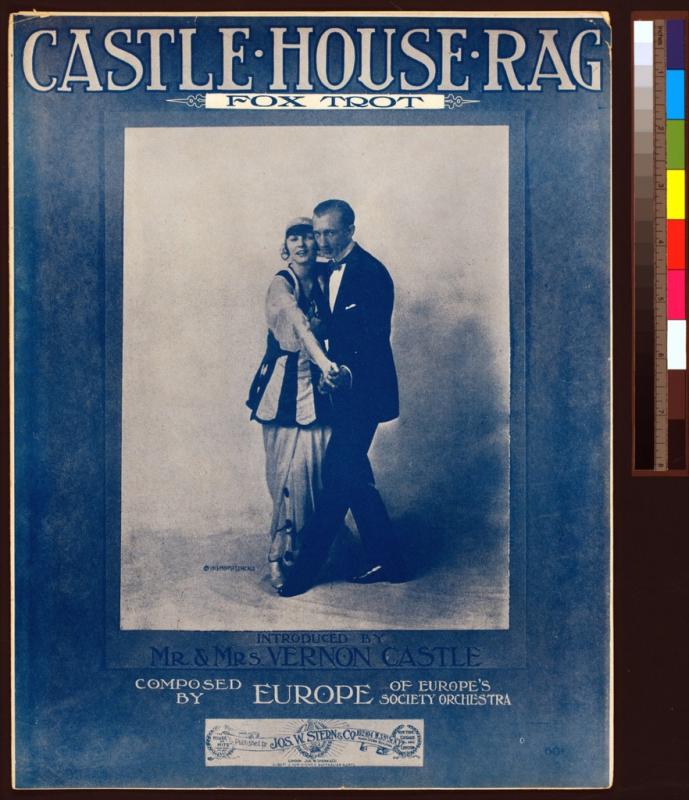

Dancers Vernon and Irene Castle were international celebrities. As dancers and dance instructors they brought “ragtime” styles like the foxtrot to audiences in Europe and the Americas: they made them accessible to middle class listeners. James Reese Europe, a formally trained African American musician from Washington DC, led the “orchestra’ that toured with the Castles. James Europe, who wrote and performed music for the theater as well as for dances, brought variety, complexity and polish to the tunes he wrote and arranged for the Castles. “Vernon was astonished,” wrote Douglas Gilbert, “first at Europe's rhythms, then at the instrumental color of his band.” The Castles hired him “as their personal musician and thereafter demanded in all of their contracts that Europe's music be used solely.” In choosing Europe to direct their band, the Castles flouted racial conventions. The decision also lent them an aura of modern sophistication and exoticism.

The recording showcases both Europe’s talents and the Castle’s range: it starts with a raucous theme and then moves through three very different styles. James Europe very consciously combined “high culture” style and forms with African American popular and folk traditions. He saw himself as counteracting the crude racial stereotypes that often dominated popular music.