Q: What was the dance craze that inspired W.C. Handy’s legendary “St. Louis Blues” (1914)?

A: The tango.

Tango music and dance emerged in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and its close neighbor, Montevideo, Uruguay, during the late nineteenth century. In 1913 and 1914, tango became a major phenomenon in Paris and New York, where the locals experienced it as both exotic and erotic. Tango was performed for spectators at swank nightclubs such as Paris's Moulin Rouge, but its basic choreography was also learned by legions of wealthy and middle-class dancers on both sides of the Atlantic.

The African-American bandleader W.C. Handy sought to tap into this popular fad. As he put it, "When St Louis Blues was written, the tango was in vogue. I tricked the dancers by arranging a tango introduction, breaking abruptly into a low-down blues. My eyes swept the floor anxiously, then suddenly I saw lightning strike. The dancers seemed electrified. Something within them came suddenly to life. An instinct that wanted so much to live, to fling its arms to spread joy, took them by the heels." "St. Louis Blues," always performed with its tango introduction, would become a standard within the blues and jazz repertoire for years to come.

The rhythmic core of the tango in this period was the habanera, a syncopated beat that had become a trans-Atlantic fad when Spanish travelers heard it in Cuba in the nineteenth century. That rhythmic motif (BUM-ba-dum-bum) is still recognizable from the eponymous aria in Bizet's Carmen. It featured in every tango of this period, and it's what gave the the A-section of St. Louis Blues the rhythmic jolt that so "electrified" Handy's audience. This musical mash-up of South American and North American genres is an excellent example of the sort of transnational fluidity made possible by recording technology in its early years.

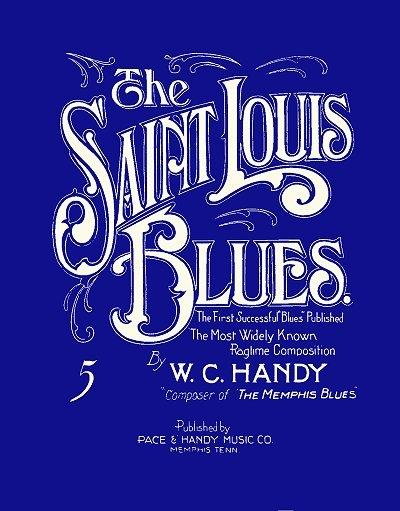

"St. Louis Blues" was also a harbinger of a crucial transformation within the recording industry. As the sheet music cover reveals, the song was published by the pioneering, black-owned company, Pace & Handy. Harry Pace was the son of a blacksmith in rural Georgia. After studying under W.E.B. Du Bois at Atlanta University, he served as business manager for one of Du Bois's magazines before going on to work for a series of black-owned businesses in the South. Pace met Handy in Memphis in 1912, and the two men went into business together. What attracted Pace was not just Handy's catchy tunes. Handy's musical education enabled him to produce written arrangements of his compositions, and these could be published. The two men realized that if they published these songs themselves and could convince artists to record them, they stood to make a tidy profit from royalties. After some early successes, they moved to New York in 1918 in order to be closer to the heart of the flourishing recording industry.

Confronting the racism of white managers and artists who refused to perform songs published by blacks, Pace and Handy began trying to convince the dominant record companies -- Victor, Columbia and Edison -- to record African-American artists. Eventually, lawsuits and the expiration of patents enabled smaller, so-called "independent" record companies to enter the market. One of these new companies, OKeh Records, issued two records by African-American vaudeville singer Mamie Smith in 1920. These were the first of the so-called "race records," which featured black artists and were aimed at black consumers, and they launched the popular craze for blues music. In 1921, Harry Pace entered the race records business, founding Black Swan Records in pursuit of both profit and racial uplift.

But in 1914, when "St. Louis Blues" was published, race records had not yet emerged. The song was frequently recorded by white artists, as in the 1921 version by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band with vocalist Al Bernard, presented to the right. As you can hear in this recording, the ODJB specialized in the polyphonic improvisation typical of New Orleans jazz. Also from New Orleans, Bernard was known for his impersonation of a Black singing style.

Note that the sheet music cover for "St. Louis Blues" describes the song as both "blues" and "ragtime." (Victor's record label called it a "foxtrot," invoking what the company considered the appropriate dance steps for the song.) In this period, popular music genres were fluid and undefined. "Blues" here likely referred to Handy's use of the term in the title and lyrics: "I got the St. Louis blues, blue as I can be." As much as anyone else, Handy helped associate the term with the 12-bar format we now recognize. Ragtime, developed by African American musicians in the Midwest, had become the most popular musical genre in the country in the 1890s. Yet "St. Louis Blues" has little in common with the famous ragtime compositions of Scott Joplin and others. As an advertising term, ragtime meant music that was syncopated, modern and, above all, Black, but ragtime music was frequently performed by whites.

Handy's song thus reveals a moment before rigid racial lines were drawn around new musical genres like the blues. Once that happened, transnational mashups like "St. Louis Blues" would become far less common.

To learn more:

- W.C. Handy, Father of the Blues: An Autobiography (Da Capo Press, 1969).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.