Q: How did recording transform music listening?

A: It brought new kinds of music into the home.

Before the advent of mass recording, music was almost always a social thing; something fleeting that people enjoyed together, in groups. Aside from concert hall performances which were only accessible to the upper class, and music made in the church, music was played in local pubs, played by children in the home, played at social dances, and also performed in salon-style gatherings or parties. While the average American may not have had the opportunity to see a concert in a large concert hall, they likely would have experienced music in the home, on the street, in parks.

The modern recording industry had its roots in the sheet music business of the early 1800s. Musicologist Richard Crawford writes that

Producers taught Americans that they could have music in their homes if they made it themselves. Their customers, sparked by artistic interest and social inspiration, learned how to become active, participating music consumers, the business was built around sheet music: not costly to publish or purchase, tailored to the skills and tastes of buyers, and hence an ideal artifact for democracy. The sheet music trade was the economic agent that, more than any other, turned the American home into a marketplace for music. And although technology has introduced many changes over the years, the same principle--distributing music in cheap, accessible units--has sustained the music business ever since.” (221-222).

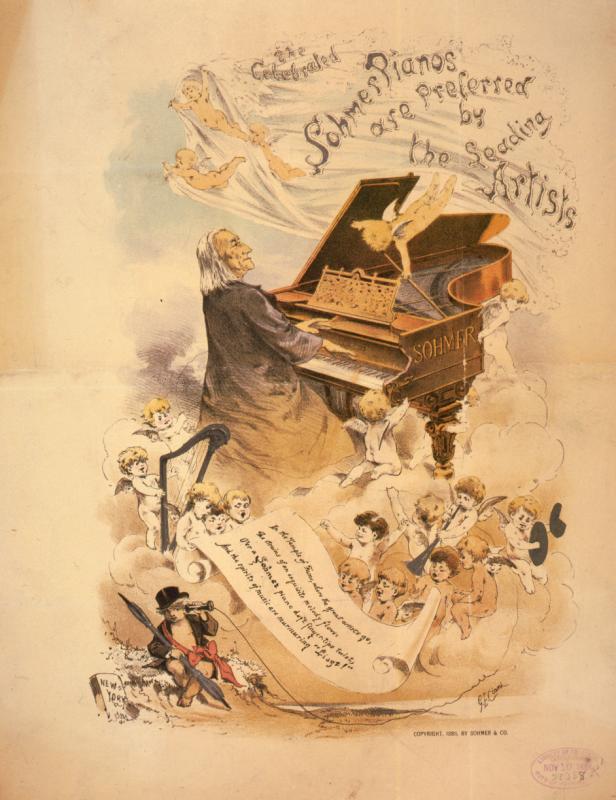

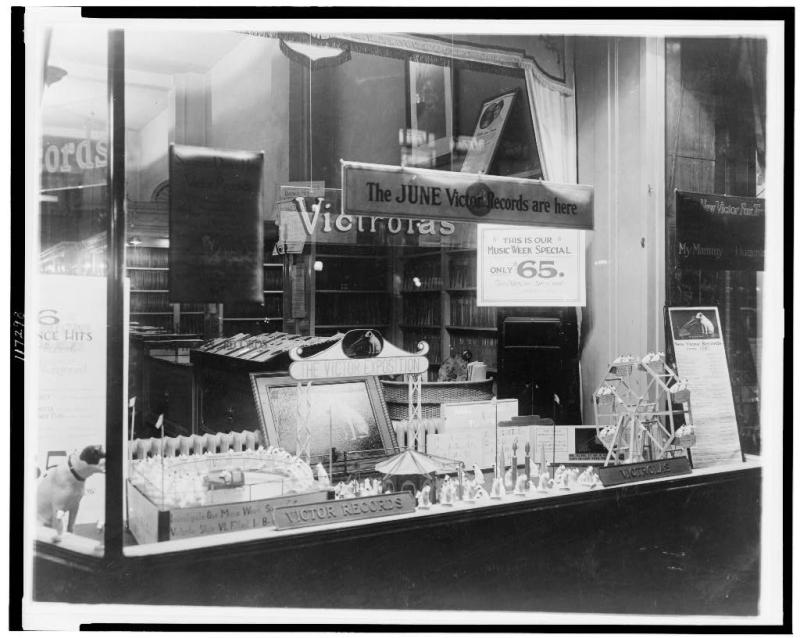

The sheet music industry encouraged the market for affordable musical instruments. Pianos, once a luxury purchase, became more affordable due to large-scale manufacturing by the 1840s. By some estimates, 1 in every 99 American households had a piano by 1900. Owning a piano during this time was seen as a sign of status, and musical get-togethers were often more focused on the social aspects than the music itself. Parents would encourage their children to learn music as a way of showing their edification, to showcase their gentility, refinement, and moral character. In the early 1900s, as recording technology advanced and phonographs became more affordable, these same middle-class consumers bought them for their homes.

In a newspaper column by Chicago journalist Finley Peter Dunne, reprinted in 1902, the Donahue family, Irish immigrants, are showing off their new piano for the neighbors

Mr Donahue asks her to play an imaginary but plausible-sounding tune, “The Wicklow Mountaineer,”

“She'll play no ‘Wicklow Mountaineer’,” says Mrs. Donahue. “If ye want to hear that kind iv chune, ye can go down to Finucane’s Hall,” she says, “an' call in Crowley, th' blind piper,” she says. “Molly,” she says, “give us wan iv thim Choochooski things,” she said. “They’re so ginteel”

“D'ye know ‘Down be th’ Tan-yard Side’?” asks their neighbor, Mr. Slavin.

“It goes like this,” says Slavin. “A-ah, din yadden, yooden a-yadden, arrah yadden ay-a.” “I dinnaw it,” says th' girl. “Tis a low chune, anyhow,” says Mrs. Donahue. “Misther Slavin ividintly thinks he's at a polis picnic,” she says. “I'll have no come-all-ye's in this house,” she says.

Recorded sound made it possible to fix music in time, and make it repeatable: it made varied private listening possible for the first time. Before recordings, an average person may have heard a single song or a piece by Beethoven only once in the home, played by an amateur musician. Once records became a part of the home, you could hear the best orchestras play a Beethoven symphony on demand. Similarly, recordings allowed fans of Vaudeville to listen to what they enjoyed on the stage in the comfort of their homes. David Suisman writes that recorded music’s “results were guaranteed. It could thrill, but it would not surprise” the listener after multiple hearings.

Individuals who had a phonograph could listen to their own music in their own time and on their own. An activity once meant to be shared in a group was now something an individual could digest privately. Although, as historian David Suisman writes: “With the rise of recorded music, listening to records emerged as a new and valuable dimension of people’s lives. Those who listened to records together sometimes forged deep affective bonds.”

Listeners could and would listen to records together and discuss what they heard. But those who could afford a phonograph could also listen to music by themselves, or in the background of daily activities. Suisman points out that the rise of recorded music also ended up ending some types of live music. Instead of a relationship forged in real time between the musician and the listener, or the musicians themselves, “music on a record existed not as a dynamic process but literally as a product—an outcome.” (267)

The transnational music recording industry allowed listeners to hear music from around the world. Argentina became a center for record factories and produced over four million records annually, and many of these records made their way to the phonographs of music listeners in the United States. Dance music, like the tango, became a success on the world stage.

Further Reading:

-

Richard Crawford, America's Musical Life: A History (NY: W.W. Norton and Company, 2001).

-

David Suisman, Selling Sounds: The Commercial Revolution in American Music (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.