Q: What city was home to two record factories pressing more than 4 million discs per year by 1926?

A: Buenos Aires, Argentina

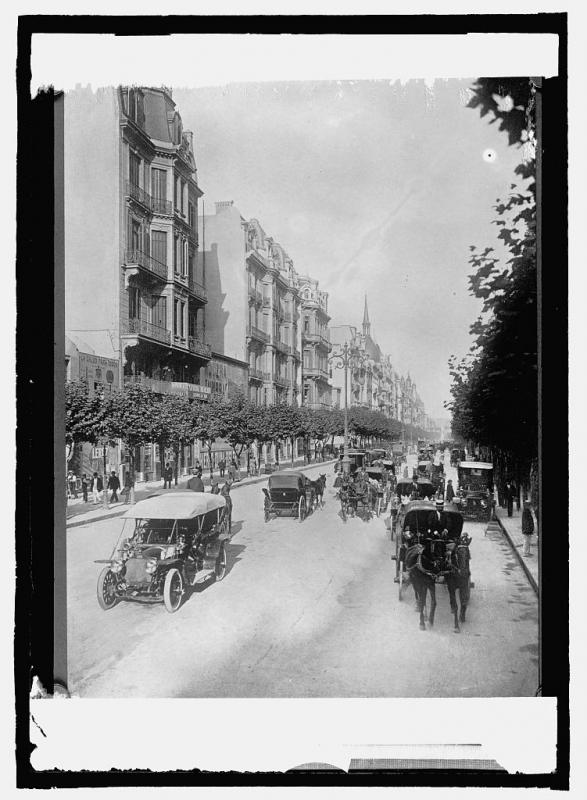

Although the early recording industry was dominated by American and European companies, the industry was a global one from its very beginning. Buenos Aires, a rapidly modernizing port city of 1.6 million people in 1914, quickly emerged as a major hub of recording activity.

As soon as the first record companies realized the lucrative potential in recorded music, they set about trying to expand the market, sending “scouts” with portable recording equipment across the globe in search of customers and material. Between 1903 and 1926, the Victor Talking Machine Company arranged more than 20 recording expeditions to Latin America, four of which stopped in Buenos Aires. During these visits, the company’s emissaries made more than 1200 recordings in the city. Victor’s main competitor in Argentina was the German company, Odeon, which began recording local artists in 1906.

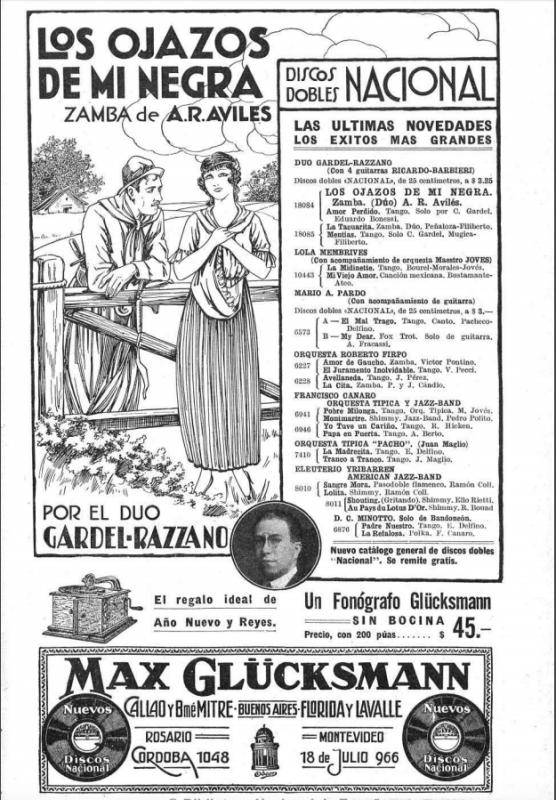

Although the record companies hoped to sell their existing catalogs in new markets, they assumed from the outset that Argentines would be especially interested in purchasing recordings of Argentine music. Victor’s North American scouts and technicians and Odeon’s German ones recognized their own lack of expertise in local genres. Therefore, they relied on local intermediaries to identify artists whose records would sell. For example, Odeon’s exclusive agent in Argentina was Max Glücksmann, an immigrant entrepreneur who was already at the forefront of the country’s nascent film industry.

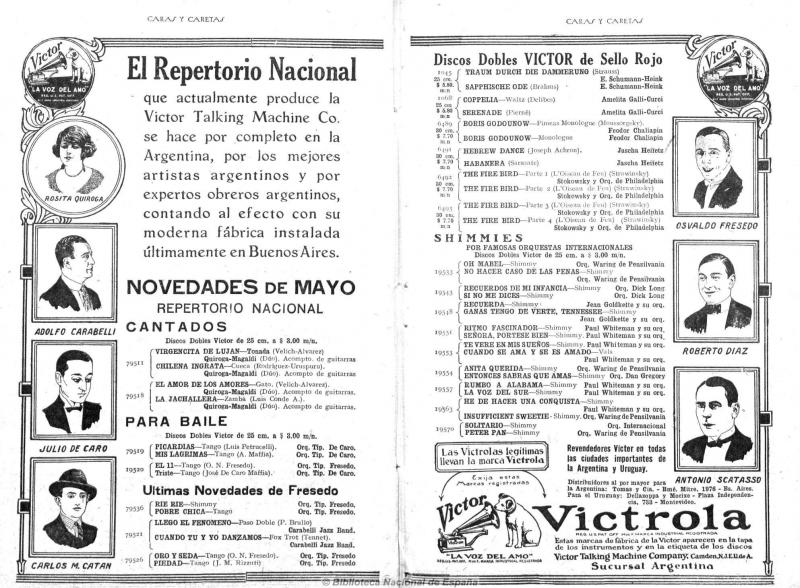

Nevertheless, record company scouts did influence the choice of what repertoire to record. These scouts were only interested in recording “local music,” which they understood as music that sounded fundamentally distinct from European and North American music. As a result, the record catalogs that Victor and Odeon distributed in Argentina were divided into two categories: European genres such as opera, considered to be of universal value, and local music, deemed to be of interest to the local market. And “local music” meant popular music; classically trained Argentine musicians were almost never recorded.

At first, the companies recorded a range of “folk” genres associated with the Argentine countryside, including the estilo and the milonga, but over time, the tango, a genre associated with the gritty neighborhoods of Buenos Aires, came to dominate the catalogs. The genre’s surge in popularity was at least partly the result of the tango dance craze that exploded in Paris and New York in 1913 and 1914. By the 1920s, Victor and Odeon were increasingly recording tango to the exclusion of other local genres. Singing stars who had begun as folk-music specialists, such as Rosita Quiroga, Ignacio Corsini, and, most famously, Carlos Gardel, became tango specialists due to the prodding of the record companies. The two recordings at right show the transformation in Quiroga's repertoire and style: from the folk tune "Siempre criolla" (1922) to the tango, "A media luz" (1927).

In this 1925 magazine ad (above), Victor lists its Argentine music on the left. On the right, the ad lists Victor’s prestigious "red-seal" classical music and, underneath, its “shimmies,” dance numbers recorded by North American jazz bands. In this way, the record company established a clear distinction between local music and “universal" genres like opera and jazz. The text at the upper left appeals to consumers’ sense of patriotism, bragging that Victor’s local music is “made completely in Argentina, by the best Argentine artists and by expert Argentine workers making use of the modern factory recently installed in Buenos Aires."

Both Odeon and Victor marketed their folk and tango recordings as authentic, Argentine music, aural symbols of national identity. Their advertisements often prominently featured national symbols such as gauchos (Argentine cowboys) and their girlfriends, known as “chinas.” Argentine consumers could indulge their desire to be up-to-date and cosmopolitan by buying opera and jazz records recorded in the United States and Europe, but when they bought folk and tango records, they were engaging with music that was packaged as their own national culture.

The competition between the record companies continued to push this culture in new directions. Pursuing their own market niches, Victor recorded the most innovative tango bandleaders, so-called “evolutionists” like Julio de Caro and Juan Carlos Cobián, while Odeon backed the more traditional bands led by Roberto Firpo and Francisco Canaro. In this way, the recording industry reinforced an enduring debate within tango music and, indeed, within Argentine national identity.

The record business grew so rapidly in Argentina that the companies established full-fledged branch offices in Buenos Aires. They also opened local production facilities in order to save on the cost of shipping master recordings to Europe and the United States and then shipping the records back to Argentina to sell. Odeon’s Buenos Aires factory opened in 1920; Victor’s in 1924. By this point, Buenos Aires was a regional center for recording. Artists from neighboring Uruguay, Paraguay, and Chile came to record in the Argentine capital, and both Victor and Odeon sent a steady stream of records to satisfy these markets.

The advent of the record business triggered an intense process of globalization, and yet it did not lead to musical homogenization. From the beginning, American and European record companies catered to what they saw as distinct musical preferences in foreign markets. Moreover, musical influences did not flow equally in all directions. With very few exceptions, Victor and Odeon marketed the music they recorded in Buenos Aires only to Latin American consumers.

Thus, while jazz music exerted a profound and lasting impact in Argentina, the tango’s influence in the United States diminished after the dance fads of the 1910s and early 1920s. The tango that Americans heard in subsequent decades was generally an exoticized and Americanized version. The trumpets, maracas and habanera rhythm in this tango recorded by Victor’s house band in 1923 made it sound quite different from the Argentine tango of the day (compare it to "Mi refugio" or "La cumparsita" above). North American record buyers remained completely ignorant of the major developments that transformed Argentine popular music in the 1920s and beyond.

To learn more:

-

María Cañardo, Fábricas de músicas: Comienzos de la industria discográfica en la Argentina (1919-1930) (Buenos Aires: Gourmet Musical, 2017).

-

Andrea Matallana, Qué saben los pitucos: La experiencia del tango entre 1910 y 1940 (Buenos Aires: Prometeo, 2008).

-

Karl Hagstrom Miller, Segregating Sound: Inventing Folk and Pop Music in the Age of Jim Crow (Durham: Duke, 2010).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography