Q: Who was the first Black blues singer on record?

A: Mamie Smith

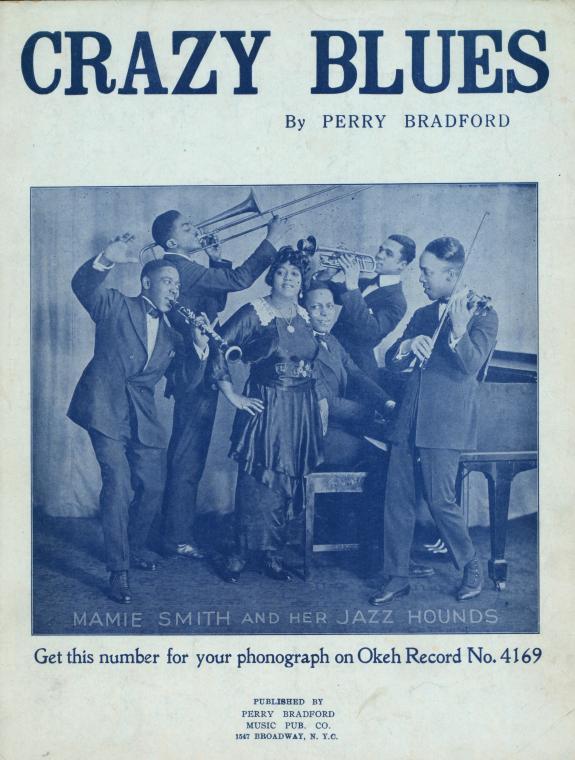

Smith was a veteran of the vaudeville stage when songwriter Perry Bradford sought her out to record the blues for Okeh Records. Smith and Bradford worked together in 1918, when she was cast in his musical revue "The Maid of Harlem.” In February of 1920, Mamie Smith recorded the blues songs “That Thing Called Love” and “You Can’t Keep a Good Man Down,” (filling in for the white singer Sophie Tucker, whom the executives at OKeh had originally wanted). In August of the same year, Smith’s recording of Bradford’s “Crazy Blues” became a crazy success, selling over one million records in a year’s time, many bought by Black Americans. Daphne Duval Harrison, author of Black Pearls, writes that the record “set off a recording boom that was previously unheard of,” and that her success finally convinced the record companies that there was a viable “market in the black community.”

Smith was not, however, the first musician to record the blues. White performers like Tucker as well as lesser-known stars like Al Bernard, Marion Harris, and Norah Bayes, had recorded blues throughout the previous decade. These artists made their careers in minstrelsy and in early recordings singing stereotypically Black music. As an established performer on the vaudeville stage, Mamie Smith sang in a style that was similar to that of white blues singers like Harris or Bayes. Listeners to her first records may well have had difficulty identifying her race. In her 1920 version of "You Can't Keep a Good Man Down," Smith's classical vibrato is similar to the vocal style of white singer Marion Harris, in her recording of "I Ain't Got Nobody Much."

Harrison writes that “Smith’s artistic versatility led her to becoming what we might think of as a curatorial bridge figure of sorts whose ‘Crazy Blues’ connected Black musical theater to evolving blues culture.” Before “Crazy Blues,” record companies largely neglected Black musicians. Nevertheless, Black women performers were able to find work and sometimes fame on the theater circuits. While these shows often perpetuated blackface tropes, they also helped popularize new musical styles created by Black performers. As Harrison suggests, Mamie Smith’s early recordings were extensions of her theatrical performances. Meanwhile, Bradford’s approach to songwriting, like that of W.C. Handy, involved packaging southern authenticity for both Black and white audiences in the North. “Crazy Blues,” itself, was a theatrical version of an ostensibly southern blues. While the structure of the song includes alternating vaudeville blues and pop choruses, the recording also includes more identifiable blues tropes like the trombone slurs heard here.

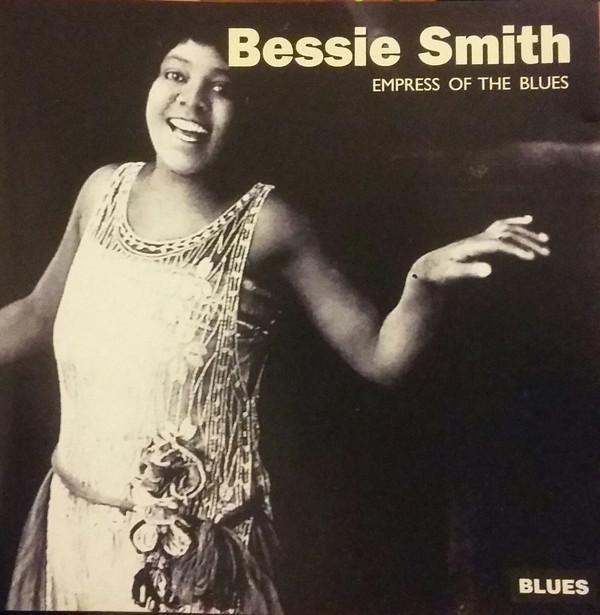

Ironically, this recording and the many other race records that followed would exert a powerful influence on the southern blues musicians of the 1920s and 1930s. Thus, music that can sound today like a direct reflection of Black southern life actually bears the imprint of vaudeville theater and commercial recordings. Mamie Smith’s theatricality likely inspired the persona of the “Blues Queen.” Harrison writes that Okeh’s successor, the General Phonograph Corporation, began promoting Smith’s recordings by linking them to her stage appearances, which ended up being a successful strategy that boosted both her stage and recording careers. According to Harrison, Smith “set a standard for the blues queens who followed her with her lavish costumes and scenery.” Her confident stage presence, with her glitzy form-fitting gowns, became the standard for black women singing the blues. Not only did it show record labels that there was a market for the music of black women, but her success paved the way for southern black musicians like Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, who also got their start on the theater circuit stages. Their work led to the more identifiable blues of the later in the 1920s, like Rainey's "Barrel House Blues" recorded in 1923.

While modern audiences might tend to associate the genre of “the blues” with southern black musical traditions, Mamie Smith’s story challenges these narratives. Born in Cincinatti, Smith perfected a style of blues singing that was more reminiscent of the blues heard on the vaudeville stage. The success of her early records in Black communities opened the floodgates to so-called “race records” by convincing other record labels to record Black artists. In her book Liner Notes for a Revolution, Daphne Brooks writes that "Mamie’s smash calls out to us to rethink our standard narratives of the blues as well as the gutsy complexity of Black women’s musicianship more broadly."

Further reading:

- Daphne Brooks, Liner Notes for the Revolution : The Intellectual Life of Black Feminist Sound (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021).

- Daphne Duval Harrison, Black Pearls: Blues Queens of the 1920s (New Brunswick, N.J: Rutgers University Press, 1988).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.