Q: What surprised record companies most about the music consumers wanted to hear?

A: The enormous demand for "ethnic" recordings.

The inventors of recorded sound weren't sure how people would use the new technology. Edison imagined that managers would record messages for their staff, or that people would record their last will and testament or a message loved ones could play after death. Edison’s company believed that recording, rather than listening, would attract consumers more. An Edison cylinder machine could record sounds as well as play them. The rival disk machine, pioneered by Emile Berliner, typically only played pre-recorded sounds.

Record companies at first had little idea of their customer’s desire and as David Suisman notes, had to invent their own market, much as modern companies often have to “educate” consumers about how to use new products. By 1910 at least the market was increasingly dominated by pre-recorded “records” in either cylinder or disk form.

Record companies initially recorded and marketed classical music and popular vaudeville performers, people who already had a reputation onstage. Early “ethnic” artists included the Italian Opera star Enrico Caruso and the Irish Tenor John McCormack, both of whom reached listeners outside of their own nationality. Both sang classical music or more formally composed songs intended for the commercial stage. Many immigrants, however, wanted to hear the music of their homelands.

Before 1924, when immigration was sharply restricted, the United States attracted immigrants from around the world. Police in Chicago, for example, by 1902 listed more than 32 different ethnicities and nationalities among people they arrested. Record companies began to realize that these immigrants wanted to hear the music of their native lands. In 1909 the Columbia Phonograph Company urged its dealers to:

remember that in all large cities and in most towns there are sections where people of one nationality or another congregate in ‘colonies.” Most of these people keep up the habits and prefer to speak the language of the old country. Speak to them in their own tongue, if you can, and see their faces light up with a smile that linger and hear the streak of language they will give you in reply. To these people RECORDS IN THEIR OWN LANGUAGE have an irresistible attraction, and they will buy them readily.

In the 1910s Ellen O’Byrne, born in Ireland, ran a record store on Third Avenue in New York City. Irish people would often ask her not for the commercial Irish songs of the vaudeville stage, but the tunes they grew up dancing to in the old country. Her son recalled “Irish people were always coming in and asking for old favorites like ‘The Stack of Barley.’ Well, she’d no records to give them because there weren’t any.” She sent him to Gaelic Park, an Irish social club in the Bronx, where he found two musicians playing old Irish tunes on accordion and banjo. In 1916 she brought them to Columbia Records and convinced them to record “The Stack of Barley.” “The five hundred records sold out in no time at all,” her son remembered.

The Vaudeville performer Patsy Touhey recorded a series of solo tunes played on the Irish Uilleann pipes in 1919: these solo recordings matched what immigrants from rural counties might have heard at local dances, which typically involved a single piper or fiddler.

More “Americanized” forms of Irish music began to appear, recordings which featured piano, guitar, and other instruments along with the more familiar pipes and fiddles that dominated folk music.

By the 1920s recordings of Irish folk music by Irish immigrants to New York especially began making their way back to Ireland. These recordings, inflected by American music and the commercial world of urban immigrants offered a novel and virtuosic take on familiar tunes. The recordings of fiddler Michael Coleman had a dramatic influence on musicians in Ireland. Musician and music historian Mick Moloney concluded “his recordings were among the most enduring cultural remittances sent home to Ireland by emigrants in the New World."

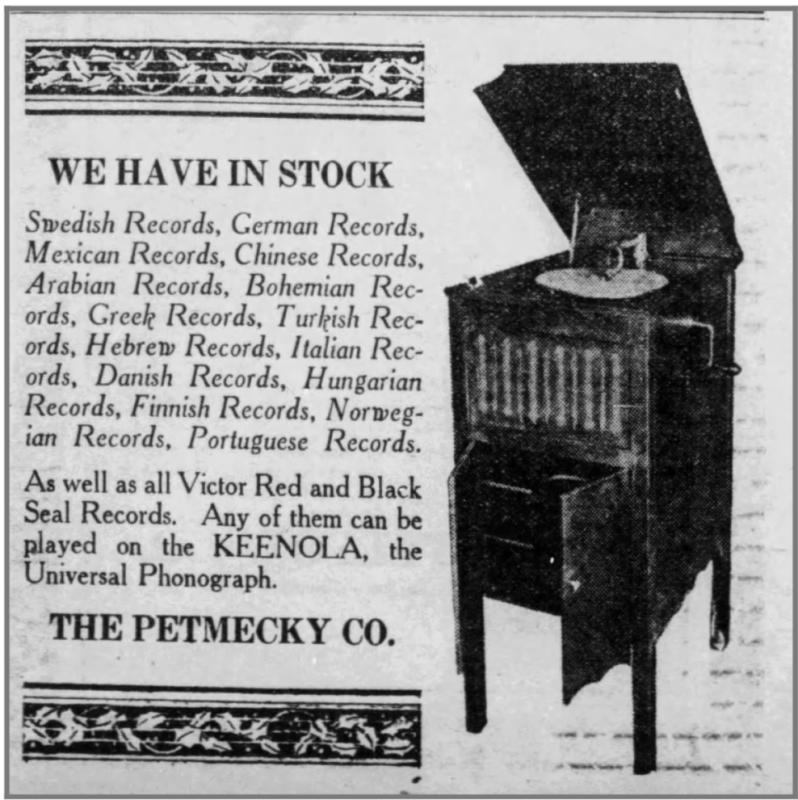

By 1916 Columbia Records offered recordings in twelve different languages, and by the time of the first world war the US had entered “the golden age of ethnic recording.” In Chicago, Wallin's Music Store issued about twenty-five Swedish records between 1922 and 1927, using the technical resources of Paramount and Autograph. Other ethnic labels of the 1920s include Gaelic, Jugoslavia, Italianstyle, Panhellenion (Greek), Parsekian (Armenian), Srpske Gusle (Serbian), La Patrie (French-Canadian), and Macksoud (Arabic).

Italian immigrants could hear opera in italian but also Italian popular tunes like "Funiculi, Funicula, excerpted here from a 1915 version by Riccardo Stracciari and Columbia Male Chorus.

The many immigrants from Sicily could find Italian songs not just in English or standard Italian but in Sicilian dialect.

Sotirios Stasinopoulos and two other unknown Greek musicians, playing the Klarino, the Greek clarinet, and the santur, similar to a hammered dulcimer, recorded “Calamatiano” in 1924.

Norwegian immigrants recorded norwegian folksongs and also American tunes in Norwegian, as in the version of “Silver Threads Among the Gold” recorded as “Sommersol til sidste stund!” by Carsten Woll in 1922.

Listeners could hear recordings in Finnish, like “Sotilas poika" recorded in 1910, or Polish dance tunes recorded on the accordion in 1921, like “Polka samo hód" by Jan Wanat.

Jewish immigrants could buy songs in Yiddish like “Havdole gut Schabes” by Lizzie Abramson.

The “golden age of Ethnic records” offered not just a snapshot of the folk music of immigrants, but also immigrants adapting the musical styles and forms of their adopted country. They give an invaluable record of earlier playing and singing styles.

To Learn More:

- American Folklife Center, Ethnic Recordings in America : a Neglected Heritage (Washington: American Folklife Center, Library of Congress, 1982).

- Richard K. Spottswood, Ethnic Music on Records A Discography of Ethnic Recordings Produced in the United States, 1893-1942 (Urbana: Univ. of Illinois Press, 1990).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.