Q: How did samba, an Afro-Brazilian genre, come to be celebrated as the national music of Brazil?

A: Thanks, partly, to the global music business.

Like the United States, Brazil has a long history of slavery and white supremacy. Moreover, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Brazilian elites were deeply influenced by the various forms of racist science being produced in Europe. Concerned about the country’s large Black and mixed-race population, many Brazilian intellectuals held out hope for the power of “whitening.” They believed that European immigrants could improve the racial stock by intermarrying with the local, dark-skinned population.

Nevertheless, in the early decades of the twentieth century, these same elites and intellectuals developed a taste for forms of music and dance associated with Afro-Brazilians. They dreamed of a white nation, but they increasingly embraced Black music. They retained their commitment to white supremacy even as they elevated genres like maxixe and samba to national prominence.

To explain this paradox, we need to appreciate the profound and surprising impact of transnational, commercial popular music in Brazil. In the late nineteenth century, Rio de Janeiro, like other cities around the world, was home to a cosmopolitan middle and upper class that was entirely plugged into transnational cultural circuits. These citizens consumed a wide variety of European music: dances like the waltz, polka, mazurka, and schottische, as well as songs in French, Italian, and Portuguese. They purchased this music as sheet music and danced to it in hundreds of live music venues. The demand for the latest European music was so strong that it was supplied not only by imported music and foreign performers but also by Brazilian composers and musicians, who themselves became specialists in these styles.

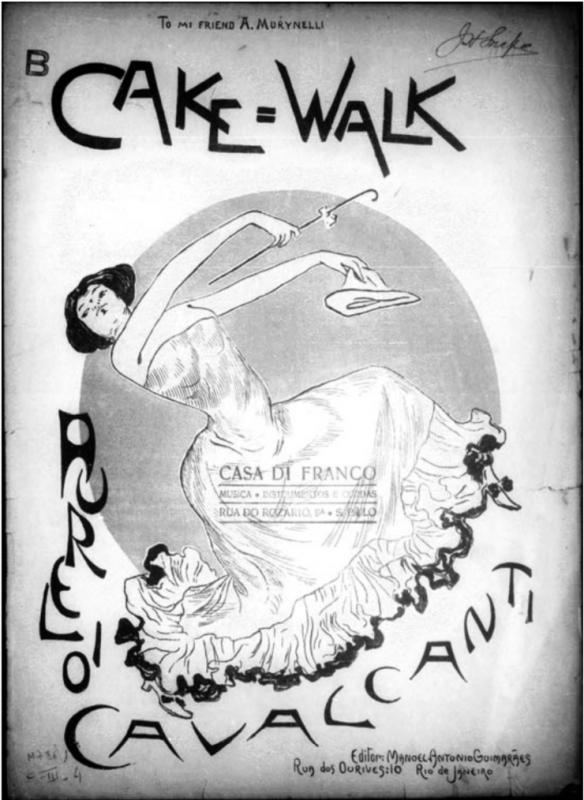

Meanwhile, in the early years of the twentieth century, Europeans were huge fans of the exotic and were increasingly drawn to Black music of all kinds. Europeans had been consuming African American music in the form of minstrelsy for decades. After the turn of the century, European capitals witnessed a series of popular fads for African American dances and musical forms: first, the cakewalk and later, ragtime and its associated dances, such as the turkey trot and the two-step. To contemporary Europeans, all of this music sounded Black primarily because it was “syncopated.” They enjoyed it because of its alleged primitiveness, its potential to liberate one from the constraints of civilization. In other words, enjoying Black music in this way reinforced white supremacy.

Cosmopolitan Brazilian consumers embraced these trends. If Europeans were listening and dancing to Black music, then so would they. The fact that Europeans enjoyed Black music meant that it was modern and prestigious to do so. Not only were the cakewalk and ragtime popular in Rio, but the European taste for Black music also created space for a new Brazilian dance, the maxixe, which combined the polka with a syncopated pattern based on the habanera. You can hear that rhythm in Ernesto Nazareth's maxixe, "Escovado." The maxixe’s syncopations sounded Black, and at this cultural moment, musical blackness was very much a virtue. The maxixe attracted audiences in Paris, New York and Rio, exerting the same transnational appeal as other Black dances. During the Carnival season of 1909, one Rio dance hall offered a “Yankee ball with the delicious cakewalk and the not less delicious maxixe.”

Black musicians played a big role in these musical trends in Rio. For hundreds of years, Afro-Brazilians had developed rich and complex musical traditions that combined West African, Afro-diasporic, and European elements. These musical practices flowered during the celebrations of the Catholic calendar and in the drumming and dance traditions known as batuque. For many Afro-Brazilian musicians, then, the new popular enthusiasm for Black syncopation represented a professional opportunity. Their blackness now functioned as a badge of rhythmic authenticity. For example, the mixed-race bandleader and composer, Aurélio Cavalcanti, specialized in the polka and the waltz but also in all the new syncopated dances: cakewalk, ragtime, habanera, tango, maxixe.

The early recording industry reinforced these trends. Fred Figner, a Jewish immigrant from what is now the Czech Republic, opened Brazil’s first recording studio in 1902 in his Rio de Janeiro store, the Casa Edison. By 1913, he had built the country’s first factory for producing records and become the local affiliate for Odeon. Casa Edison's record catalogs were originally dominated by European genres and by white artists, but given the transnational fad for black music, this began to shift. Even though Figner and other executives continued to favor light-skinned artists, there were important exceptions. Eduardo das Neves, an Afro-Brazilian poet, clown, musician, and composer became one of Casa Edison’s biggest stars. He cultivated the image of a street hustler, or malandro, a figure that would become central to samba mythology and lyrics, and he flaunted his wealth, fame, and pursuit of white women in ways that challenged Brazil’s strict racial hierarchy.

Cosmopolitan tastes helped produce the idea that Brazil’s national music was, at its roots, Black. Crucial to this process was the Oito Batutas (“Eight Aces”), a mixed-race band founded by two legendary Afro-Brazilian musicians from Rio, Pixinguinha (Alfredo da Rocha Viana Filho) and Donga (Ernesto Joaquim Maria dos Santos). Though they originally sold themselves as backwoods hicks (sertanejos) playing rustic folk music from the Northeast, they increasingly called themselves a “jazz band,” a label that shaped their choice of instrumentation and wardrobe. In 1922, they enjoyed a successful, six-month stay in Paris, an experience that cemented their status in Brazil as purveyors of national music. Both Pixinguinha and Donga would play key roles in the rising prominence of music called “samba,” even if the music they played did not sound much like the samba of the 1930s and beyond.

Just as in the United States, the cosmopolitan taste for Black music created both constraints and opportunities for Black musicians. Afro-Brazilian musicians were put into a confining aesthetic box, forced to play music that resonated with contemporary ideas about blackness. Nevertheless, at the very same moment as North American blues and jazz musicians were innovating brilliantly from within those constraints, Afro-Brazilian innovators were doing the same thing. In the end, they also created a rich, evolving tradition from what had been the object of condescending primitivism. From racism, they created art.

Further Reading:

- Marc A. Hertzman, Making Samba: A New History of Race and Music in Brazil (Duke University Press, 2013).

- Cristina Magaldi, “Cosmopolitanism and World Music in Rio de Janeiro at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” The Musical Quarterly 92 (2009), 329-64.

- Bryan McCann, Hello, Hello Brazil: Popular Music in the Making of Modern Brazil (Duke University Press, 2004).

- Micol Seigel, Uneven Encounters:Making Race and Nation in Brazil and the United States (Duke University Press, 2009).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.