Q: Why did James Reese Europe forbid his musicians to bring sheet music to gigs?

A: He was playing to white stereotypes of African Americans.

People in power often like to imagine members of the underclasses as “naturally” gifted but also primitive, passionate, and undisciplined. For example, in 1867 the English cultural critic Mathew Arnold imagined the Irish in exactly this way. “All that emotion alone can do in music the Celt has done; the very soul of emotion breathes in the Scotch and Irish airs;” he wrote, but “what has the Celt, so eager for emotion that he has not patience for science,” done in music compared with “the less emotional German?” Similarly white Americans often preferred to imagine African Americans as soulful but “natural” and spontaneous, lacking discipline.

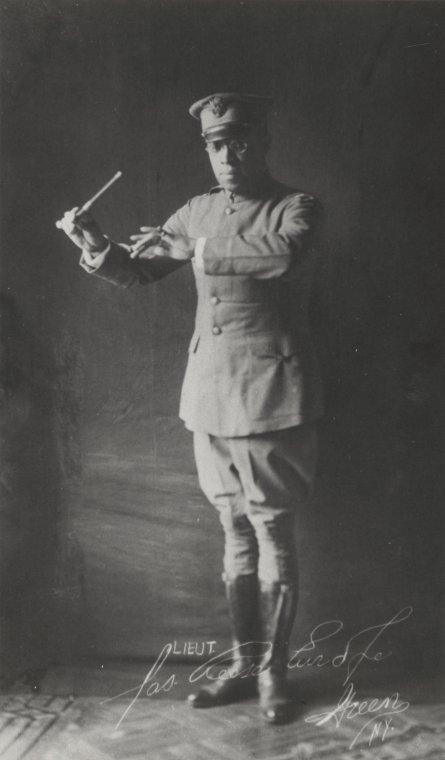

James Reese Europe was a disciplined, trained musician and a highly effective leader. In New York, Europe turned an informal organization of musicians, the “Clef Club,” into a booking agency and quasi union at a time when the formal musicians' union would not accept black members. He was able to offer clients a range of musical styles from “hot” ragtime numbers to tangoes to vaudeville novelties to polished classical music. He could easily compose and arrange music for a large military band, and conduct their performance. Despite his and his musicians formal training, he also knew that white people often preferred to imagine African Americans were “naturally” musical, or believe the music they played came from some sort of magic racial quality rather than from hard work and practice. When necessity required, he was happy to let white people believe that his musicians were naturally gifted rather than formally schooled.

At the same time, he was what was then know as a “race man,” someone committed to improving the status of African Americans, and he saw himself as bridging the worlds of European art music and African American folk traditions.

Lieutenant Europe led the segregated 369th Infantry band, the “Harlem Hellfighters” in France in WWI: the band was a sensation, combining patriotic marches with what by then was coming to be called “jazz.” Although Europe’s band included seventeen Afro Puerto Rican musicians recruited specifically because they formally well trained in music, accounts of the band still reflect the idea that black people were naturally more emotive and spontaneous. Speaking of the Harlem Hellfighters band in France, the pianist and music critic Henriette Weber wrote:

“Rhythomaniacs the Negroes have been called. Certainly they have an uncanny ability to place the accent where by all the laws of white man’s music it should not be placed. And that, if you please, is jazz. There is nothing more contagious than this peculiarly American music which our dark brothers have given us—and which so eloquently expresses our national motto, 'Step lively, please.' "

In this passage Weber struggles with how to understand Europe’s music, seeing it as both the product of a racial gift and as uniquely American and modern. James Reese Europe, in the uniform of the United States and representing the US army in France, epitomized the complex way musical meanings circulated.

To Learn More:

- Louis Onuorah Chude-Sokei, The Last “Darky” : Bert Williams, Black-on-Black Minstrelsy, and the African Diaspora (Durham N.C: Duke University Press, 2006).

- David W. Gilbert, The Product of Our Souls Ragtime, Race, and the Birth of the Manhattan Musical Marketplace (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2015).

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.