Q: Who was the first African American recording star?

A: George W. Johnson

George W. Johnson was born in the 1840s in Loudoun County, Virginia, likely to enslaved parents. His musical talent was apparent at an early age, and he eventually escaped a life of labor in the 1870s by becoming a street performer in New York City known for whistling a number of popular songs. In 1890, Johnson recorded his first song for Victor Emerson of the New Jersey Phonograph Company. Although early recording companies were primarily concerned with the possibilities of sound recordings for business dictation, Emerson convinced the company to record some popular songs as a novelty. George W. Johnson’s identifiable whistle transferred well onto early recording technology and earned him a spot among the first artists to put their voice to record.

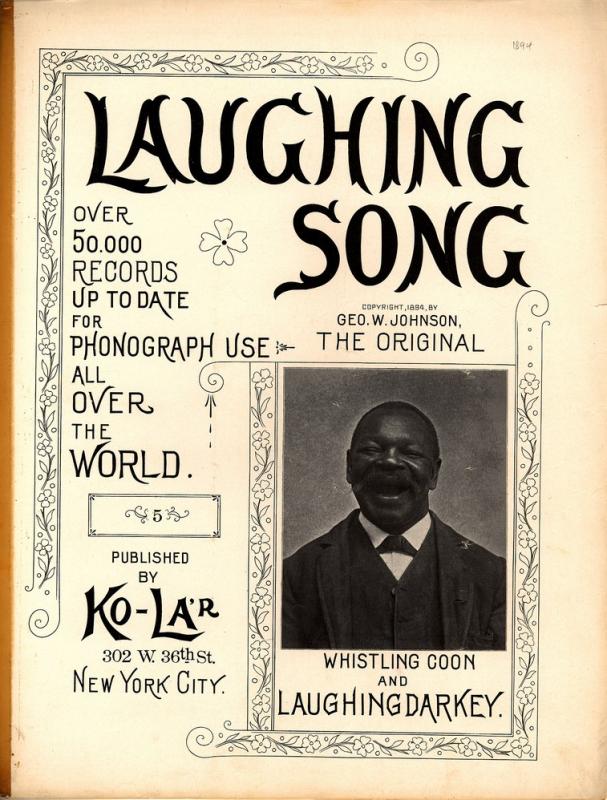

On record, Johnson quickly became a star. The first song he recorded was called “The Whistling Coon,” which featured the same signature whistle that brought him to the studio in the first place. Johnson then recorded "The Laughing Song," and this time featured his distinctive laugh. The popularity of Johnson’s songs reflect the widespread popularity of “coon songs” and other forms of racial and ethnic humor in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, coming out of a long tradition of minstrelsy.

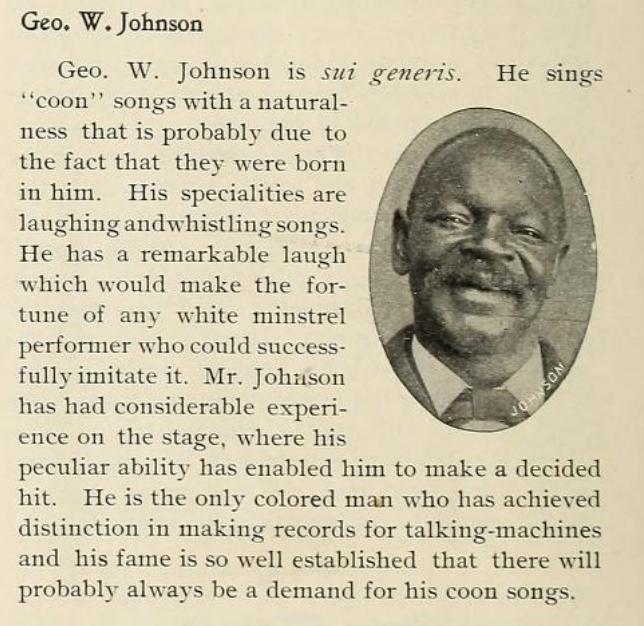

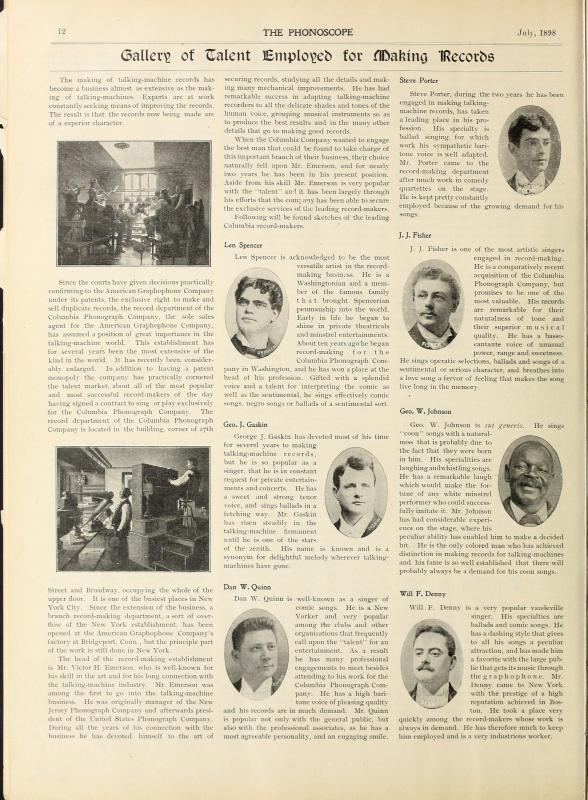

The page to the left from an 1898 issue of The Phonoscope features a description of Johnson that uses his race to suggest an authenticity in his coon songs that "is probably due to the fact that they were born in him," despite the genre's actual roots in racist stereotypes developed primarily by white performers. The page also notes that he "is the only colored man who has achieved distinction in making records for talking-machines" and Johnson is indeed the lone Black performer pictured in this "Gallery of Talent." White songwriters like Sam Devere who wrote “The Whistling Coon” and vaudeville stars like Cal Stewart who recorded his own version of "The Laughing Song" made up the majority of the commercial music industry as Johnson rose to fame. Listening to Stewart's mimicry of Johnson's distinctive laugh, we can hear the way that the visual comedy of blackface was beginning to be transformed into a sonic form of racial parody that was still dominated by white voices.

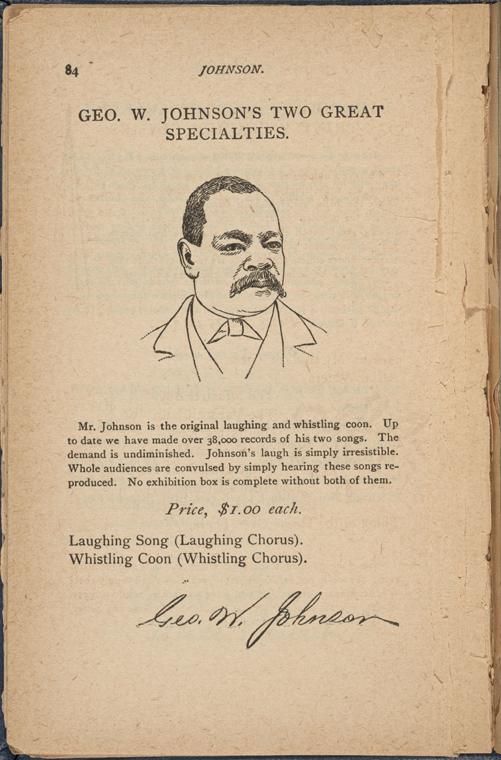

Although it is difficult to find accurate statistics on the early music industry, the page pictured to the left from the 1894 issues of The Catalog of Standard New Jersey Records notes: “Up to date we have made over 38,000 records of his two songs. The demand is undiminished.” Johnson’s primary biographer, Tim Brooks, finds this figure even higher at 50,000. Whatever the number, Johnson’s original tunes still appeared in label catalogs nearly twenty years after his original recording.

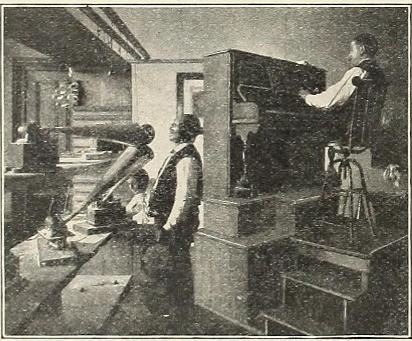

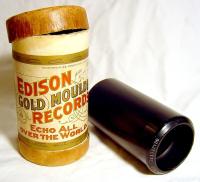

Even if the figures are inflated, recording anywhere near 38,000 cylinders during the early acoustic period of sound recording is a remarkable feat. During the majority of Johnson’s career in the 1890s, sound recordings were made on brown wax cylinders, the earliest format of commercial recording invented by Thomas Edison in 1887. To record a song, an artist would sing into a large horn, as you can see Johnson doing below, and the vibrations would cause a stylus to etch the sound into wax for playback on a phonograph machine. Because the recording was etched directly into the wax, a single performance could not be edited and would only yield 3-4 cylinders at most. This meant that Johnson spent many afternoons in the recording studio performing the same songs over and over again to produce enough cylinders to meet consumer demand.

In 1902, a new process of recording called gold moulding replaced the early brown wax process and improved upon the durability and quality of sound recordings. Rather than etching the recording directly into wax, the gold moulding process created a metal cast of the sound that was then filled with slightly more durable black wax to produce each cylinder. This innovation created the first reliable “master” track in commercial sound recording and led to more consistency in the quality of recorded sound. The new metal masters also shifted the labor dynamics of the studio. Rather than long days performing the same song over and over, the new metal masters allowed for the mass production of a single performance and increased the commercial viability of a sound recording industry focused on music.

Because cylinders are not a very durable medium, few remain and an even smaller portion of those are difficult to listen to due to low volume or loud hisses and pops. Performances at the time also had to take the limitations of wax cylinder recording into account which affected the kinds of musical arrangements we hear on early records and even resulted in the creation of new instruments like the Stroh Violin. There was also nowhere to print the name on the wax cylinder and their cardboard cases were mass produced to promote the cylinder Edison, not the recording on it. Sometimes slips of paper were included in the case with the song and artist name on it, as you can see on the left, but these were easily lost. To make sure the recording could be identified, as you can hear in this 1902 version of "The Laughing Song," an announcer would name the singer, song, and company before the performance began. This also meant that visual culture remained remained a primary mode of marketing cylinders to consumers, as you can see in the image below. The sheet music features an image of Johnson in mid-laugh with the terms "Whistling Coon and Laughing Darkey," again suggesting to potential customers that Johnson's performances of coon songs are authentic expressions. Being pictured in a suit also provides a visual representation of the "dandy darkie" that is the subject of the song song's lyrics, especially appealing to an audience used to the visual comedy of the minstrel stage.

We can hear all of these technological shifts and genre conventions in what remains of Johnson's recordings. For example, listening to three digitized versions of “The Laughing Song,” all recorded on brown wax cylinders in 1897, makes audible the variations in quality and performance in early sound recording. In the first, the verses are much lower than the choruses, where we clearly hear his distinctive laugh, loud enough to cut through the wax of the cylinder. When he is not singing however, the piano accompaniment, which would have been positioned further away from the horn, sounds much more distant and is overshadowed by hisses and pops. On another cylinder, the the piano is more balanced with Johnson's voice although both are accompanied by a steady layer of static, slightly less distracting than the hisses and pops in the first example. A third cylinder from the same year is perhaps the most unlistenable of the three. Johnson’s distorted voice again overshadows the piano but is buried under so much static, hisses, and pops that it is difficult to focus on the his voice or the music underneath. Although the quality of this record is due in part to age, inconsistencies in sound quality were also a feature of the media in its time. Listening again to the choruses on each cylinder also lets us hear the slight deviations in his laugh, a reminder that each cylinder reflects a distinct performance rather than a copy of a single version.

Comparing these three recordings to a gold moulded cylinder recording Johnson made around 1902 lets us hear just how much this technological improvement changed the listening experience. Although there is some slight static, Johnson’s voice is much louder and clearer. It also allows us to better hear the verses about the "dandy darkie" who is the subject of the song, and marketed to be associated with Johnson himself. The lyrics reflect the kinds of minstrel tropes popular at the time, with lines such as "His mouth is like a trap, And when he opens it gently, You will see a fearful gap." The musical accompaniment is also more balanced with Johnson’s vocals, and we can hear expanded instrumentation of piano and horns possible because of improvements in recording technology.

Despite his massive success in the 1890s and 1900s, George W. Johnson eventually found himself edged out of the recording industry. After struggles with substance abuse and an acquittal in the muder case of his wife, he reportedly spent the last years of his career under the stewardship of white vaudeville performer Len Spencer. However, the industry was changing and Johnson never regained the fame or income he earned during his early days of recording. George W. Johnson died on January 23, 1914 and is buried in Maple Grove Cemetery in Queens, New York.

By the time of his death, Johnson’s legacy as the first--and virtually only--Black recording artist during the first decades of the music industry was being built upon by new talent. For example, African American vaudeville star Bert Williams recorded his widely popular song “Nobody,” which drew on the same kinds of racial stereotypes that we hear in Johnson’s earlier music. Performers like James Reese Europe offered a more serious and “respectable” style of music at the same time that Blues became a popular recording genre due to the work of W.C. Handy and "blues queens" like Mamie Smith. The development of the race records genre, indicating music made by and for Black Americans, further entrenched the racial segregation of the music industry despite increasing opportunities for Black recording artists.

Further Reading:

- Tim Brooks, Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005).

- Tim Brooks, "The Laughing Song”—George Washington Johnson," Library of Congress, 2013, https://www.loc.gov/static/programs/national-recording-preservation-board/documents/LaughingSong.pdf.

- "Cylinder Recordings: A Primer," UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive, https://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/history.php.

Find even more on this topic in our bibliography.